The quantity of information about pet nutrition, and the number of brands and diets, can be overwhelming for pet owners.

Unfortunately, much of the information provided – for example, on some “advisor” websites – is poor, with little in the way of scientific evidence. Many pet owners find choosing the right food for their pet difficult (PetfoodIndustry.com, 2015).

While all the areas of dietary management of dogs and cats is beyond the scope of this article, this will cover the basics of understanding how to choose a diet for a healthy pet.

No one right diet exists for all dogs or all cats. The basic requirement for a diet is that it is complete and balanced; that is, has all the nutrients required in the correct amounts, for the right species and the right life stage.

Some foods sold are meant to be complementary (for example, treats) and not fed as the sole food. The label should state whether it is a complete or complementary diet (The European Pet Food Industry [FEDIAF], 2019; Figure 1).

Life stage

Nutritional life stages include growth (puppies and kittens), adult maintenance and reproduction (pregnancy and lactation).

Most good diets for growth are also adequate for reproduction. Pregnant dogs need a puppy or gestation diet during the final third of pregnancy, and cats should be fed a growth or gestation diet from the time of conception.

If a diet states “complete for all life stages”, it is a diet for growth and may not be appropriate for some older pets, overweight pets or pets with some disorders. “Senior” or “geriatric” is not considered a life stage as the requirements for older pets vary considerably for the individual pet.

Special dietary considerations in otherwise healthy animals include obesity and hard work, or exercise. The calorie density (for example, kcal/100g) of the diet should be low for those that gain weight easily, or appropriately high for pets that tend to be thin or have a very active life.

This calorie content information is not required on the pet food label in the EU, although it may be obtained from some companies or estimated by a calculation. The Pet Food Manufacturers’ Association website provides an online calculator to estimate calorie content from the nutrient information on the label.

Many working – and some show – dogs will need more food and calories than the amounts recommended on the label for less active pet dogs. If it isn’t possible or healthy for the dog to eat more during meals, providing an extra meal (for example, in the afternoon) can help. For owners who are not home at this time, an automatic feeder is useful.

Some working dogs also require a bit more protein in their diet than a relatively inactive dog. Therapeutic weight loss diets are the best choice for overweight pets needing to lose weight and activity feeders can be helpful (Figure 2). Feeding less of a maintenance diet to decrease calorie intake risks a deficiency of nutrients as all of the nutrient intakes will be decreased.

Light diets

Products that are labelled “light” (or “lite”) without reference to a specific nutrient or other substance (for example, light in XX) means a reduction in energy (calorie) content, compared to a comparable pet food. The energy density of the product should be at least 15% lower than a comparable standard adult maintenance pet food within the same brand. These diets are often not calorie-restricted enough for weight loss.

Regulation of commercial diets: how do you know a diet is complete and balanced?

In the EU (and the UK), if a food claims on the label that it is complete, the diet should meet the FEDIAF nutrient requirements and these can be found on its website.

The regulation is that the food is complete based on computer formulation. Many food brands also undergo feeding trials. Feeding trials mean the food not only met the nutritional profile by formulation, but was also fed to healthy animals to demonstrate adequacy. This helps determine if problems exist with food assimilation or digestion, and interactions between nutrients.

Reading pet food labels

The principal display panel, usually on the front of the bag or package, contains required information about the target animal species – for example, “food for cats”, the net wet weight. It may have bursts and flags – for example, “new and improved”, “preferred by cats everywhere” and a product picture.

The statutory and regulated part of the label includes the ingredient list in descending order by wet weight, and the typical analysis. In the EU, the ingredient list can be listed individually or by general category terms – for example, lamb, rice, chicken, maize or “meat and animal derivatives”, and “cereals and derivatives of vegetable origin”. The ingredient list may or may not be an indicator of quality.

Meat derivatives include “by-products” or “secondary products”. These are the part of a slaughtered animal humans choose not to eat, often for cultural reasons, rather than nutritional ones. These meat products are from animals that have passed veterinary inspections as being fit for human consumption at the time of slaughter; that is, all the meat ingredients in all EU pet foods are “human grade”.

Many by-products or meat derivatives are a good source of nutrition, and their use in pet foods means these parts of the slaughtered animal are not wasted. It also means less competition with the human food chain exists than if meats humans like to eat are used in pet foods.

Without the use of by-products, many owners would not be able to afford to feed their pets a compete and balanced diet. Furthermore, without their use in pet foods, many of these products could end up in landfill, where they could potentially contaminate the water supply, or be incinerated, releasing undesirable amounts of CO2 and smoke into the air.

The typical analysis on the label includes percentages of crude protein, crude fat or lipid, crude fibre (mostly insoluble and non-fermentable fibre), and ash. The amount of moisture should be on the label if it is more than 14%.

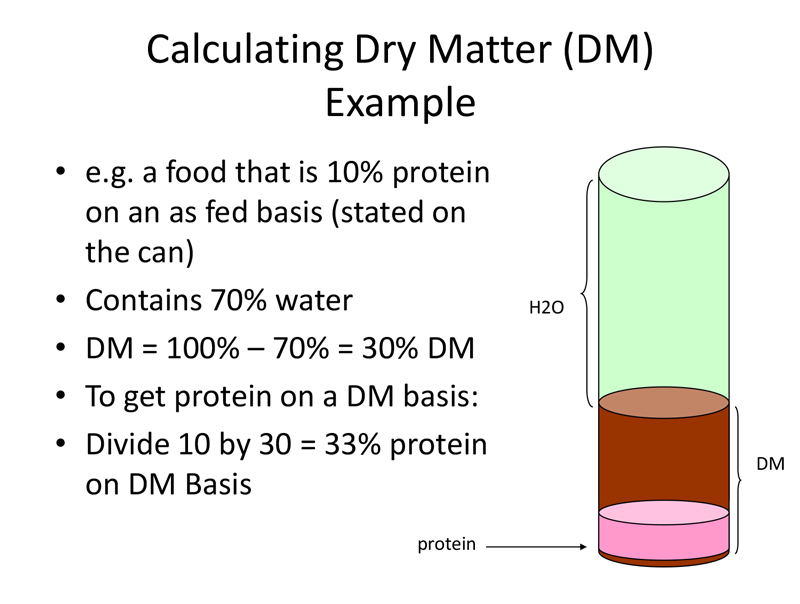

Many owners find understanding the nutrients in wet versus dry foods confusing and converting these to dry matter is helpful. Dry matter is determined by subtracting the moisture content in a wet food from 100g. For dry foods, an estimate of 10% moisture may be used for dog foods and a bit less, around 7%, for dry cat foods. The percentage of the nutrient is then divided by the dry matter to determine its amount on a dry matter basis (Figure 3).

Comparing diets

What makes a diet expensive?

More expensive diets may use high-quality ingredients. They also may use a fixed formula, so the diet contains the same ingredients every time, regardless of cost. Open or variable formulae use ingredients that meet the label requirement, but may vary depending on the cost – for example, either turkey or chicken for poultry. Pets that have a food sensitivity may require a fixed formula diet; others, which are the majority of the pet population, are much less likely to require a fixed formula diet.

Some larger companies also have very high-quality control of their ingredients and processing. Finally, some diets have added “functional foods”, such as added antioxidants, prebiotics, omega-3 fatty acids, L-carnitine, chondroitin sulphate/glucosamine, green-lipped mussel extract or other ingredients with a positive effect on health.

Some additional cost may be due to marketing on quality claims that don’t improve nutritional quality – for example, grain free or gluten free.

Diets labelled premium or super-premium may fulfil some, or all, of these examples of what makes a diet more expensive; however, the terms are not regulated, so they may also be used on any packaging and it isn’t possible to know what they reflect.

Marketing and labeling terms

Hypoallergenic has no meaning as a general term, as what an individual is sensitive to depends on the exposure. Human-grade food is also ambiguous and has no EU regulation. “Holisitic” on a label means absolutely nothing; no legal definition or regulation of the term exists.

“Natural foods” are perceived as better or more wholesome by some owners, although only definition guidance exists, but no legal definition or regulation. In the UK, the Food Standards Agency states a “natural” product is comprised of ingredients produced by nature, not the work of man or interfered with by man. They should have been subjected only to such physical processing as to make them suitable for pet food production and maintaining the natural composition. Feed materials and additives containing, or derived from, genetically modified organisms also exclude use of the term “natural”.

The definition of “organic food” varies in different parts of the world. In the EU, it generally means avoidance of synthetic chemical inputs, irradiation and the use of sewage sludge; avoidance of genetically modified seed; use of farmland that has been free from prohibited chemical inputs for a number of years (often three years or more); adhering to specific requirements for feed, housing, and breeding of livestock; detailed written production and sales records (audit trail); strict physical separation of organic products from non-certified products; and periodic on-site inspections.

FEDIAF discusses the use of the term “free from” (for example, grain, gluten and so on) stating: “These negative claims or claims on absence should not directly, indirectly or implicitly: be used if all similar goods in the same category or class or all pet food do not contain the substance in question; [or] give the impression that products containing that particular substance/feature are dangerous”.

Functional claims on foods

Some diet ingredients can potentially have a positive effect on health (for example, support immune function) and reduction of disease risk (for example, decrease the risk of developing joint disease). A functional claim describes the effect of a pet food or nutrient, component, or additive in the pet food on growth, development or normal functions of the body that provides a specific physiological benefit.

These claims need to avoid stating the diet will prevent or treat a disease, as the food then may qualify as a drug and have different regulation. Drawing particular attention to a nutrient will require its declaration either in the composition or analytical constituents.

Grain-free diets

Grain-free diets are not necessarily low-carbohydrate diets, as grains are an ingredient and carbohydrate is a nutrient. Ingredients other than grains can provide carbohydrates.

Cooked grains are generally well digested by dogs and cats, and provide nutrients, including energy, protein, vitamins and minerals. No proven benefit exists for grain-free diets, and an association exists with canine dilated cardiomyopathy and the feeding of grain-free diets. The causation has not been determined and safe grain-free diets may exist.

Protein

Should a meat ingredient – for example, poultry or beef – be the first ingredient on the label? Are high protein diets better?

Firstly, protein is a nutrient, and can be provided by various animal and plant ingredients. When the protein ingested is more than what is required for the body, the ammonia group of the protein is removed and excreted in the urine as urea.

The carbon skeleton part of the protein is generally used for energy or stored as fat. This makes excess protein an expensive method of providing energy, as carbohydrate sources are less costly and fat sources are higher in calories (if that is what is needed). It is also less sustainable than just using the amount of protein in the diet the animal can use.

Conclusions

Much of the information on the internet about pet foods is not based on scientific evidence, although some good resources exist (see references and further reading).

Many different diets will meet the requirements of being complete and balanced for the right life stage of a dog or cat. The choice of diet should be made based on the reputation of the company, its use of feeding trials, in addition to computer analysis of their diets and their quality control.

Trends or fads, such as grain free or holistic, do not add to the value or quality of the diet, and are usually done for marketing, rather than pet health.

The list of ingredients on the label does not necessarily reflect the quality of the diet.

Leave a Reply