Recognition of poor mobility is important, and all practice staff are key in helping to identify and aid in the treatment of mobility issues.

Good communication between the different veterinary teams and paraprofessionals, as well as between the practice and the owner, are paramount to recognising, treating and maintaining a patient’s mobility.

Reception staff can recognise a patient in discomfort while they are in the waiting room; for example, a dog that keeps shifting its weight on its forelimbs – this can be flagged up to clinical staff on the practice management system or in person.

Vets, through their consultation process, clinical examination and investigations, will provide a diagnosis and treatment plan.

The RVN is ideally placed for developing and implementing nursing care plans that are tailored to an individual’s needs, and for advocating for their patient – both within the hospital environment and beyond – ensuring appropriate advice is passed on to owners.

This article looks at what mobility is, the causes of poor mobility, and modalities that can be employed to aid and improve mobility. It also looks at mobility clinics and the role the RVN plays in championing for their patients.

What is mobility?

Mobility is defined as the ability to move easily, and without restriction or pain (Ramos and Otto, 2022). It is the ability of the dog or cat to move around its environment, and partake in normal activities of daily living.

Normal mobility occurs because of the interaction between the bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments and fascia of the musculoskeletal system, and the nerves of the neuromuscular system, including the peripheral and central nervous systems.

Mobility is influenced by an individual’s conformation, posture, proprioceptive awareness, muscle condition and body condition.

What causes poor mobility?

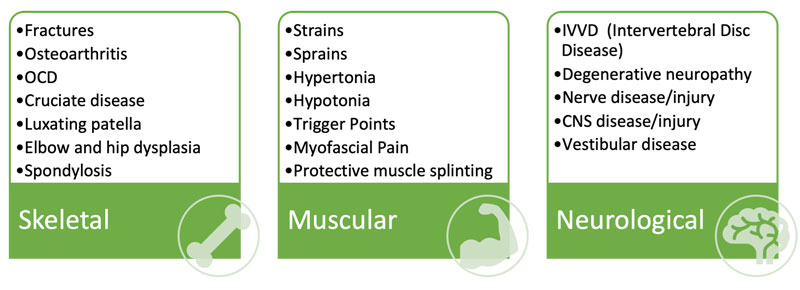

Poor mobility can generally be attributed to dysfunction of the musculoskeletal system, or dysfunction of the peripheral or central nervous systems.

Changes to mobility may occur suddenly because of an injury or trauma, or the patient may have a history of chronicity due to a disease of specific joints, soft tissue structures or by a neurological disease to the brain, spinal cord or peripheral nervous system.

Some conditions that can contribute to poor mobility are detailed in Figure 1.

Many of these conditions result in long-term, chronic mobility problems, such as osteoarthritis (OA), degenerative neuropathies, and hip and elbow dysplasia.

Maintaining mobility in these patients is critical for them to be able to enjoy a good quality of life and undertake the normal activities of daily life.

A variety of conditions are seen concurrently; for example, OA – a degenerative disease affecting synovial joints and typically seen as pain or inflammation of the joint(s) – can be associated with myofascial pain, hypertonia of overcompensating muscles and protective muscle splinting of the joint(s) concerned.

A fracture of the radius and ulna may result in peripheral nerve damage, and vestibular disease may result in hypertonia, and trigger points of the neck and forelimb musculature.

A comprehensive and systematic approach to assessment will provide the information required to localise and diagnose the patient’s condition so an appropriate treatment plan can be put in place.

Mobility and pain

Pain is the clinical sign associated most often with poor mobility. The scope of this topic is too large to be included in this article; however, the management and treatment of hyperaesthesia, wind-up and allodynia, seen frequently with extreme cases of OA pain and poor mobility, must not be overlooked.

What are the clinical signs of poor mobility?

Gait changes

- Lameness, which is often identified in pets by the owner who then seeks veterinary advice, can also be seen by a veterinary surgeon during a routine clinical examination. Most dogs and cats are lame because they cannot, or will not, use one or more limbs in a normal way. Lameness is an indication a patient is in pain and discomfort, as it is an avoidance behaviour.

- Stiff when walking/getting up.

- Abduction or adduction of a limb(s).

- Pacing – a gait pattern in which the ipsilateral limbs move simultaneously as a pair.

- Crabbing – a gait pattern in which the animal’s body is at an angle to the line of travel.

- Hopping/skipping/single tracking.

Postural/anatomical changes

- Postural changes, such as lordosis and kyphosis. Subtle changes in posture such as a kyphotic spine during a sit may indicate an injury or underlying musculoskeletal problem.

- Poor tail carriage.

- Plantigrade stance of carpi or tarsi.

- Scuffing of limbs – poor proprioception.

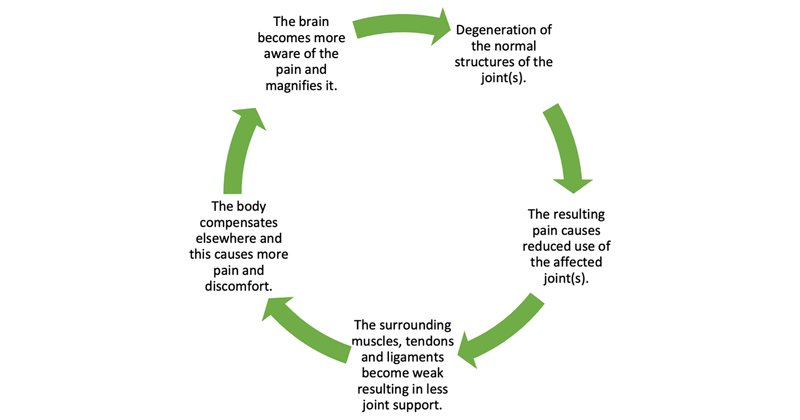

- Muscle atrophy because of reduced activity due to pain. This becomes a self-perpetuating problem (Figure 2).

Inability to perform normal activities of daily living

- Reduced exercise intolerance – struggling and slowing down on walks.

- Difficulty rising from lying down.

- Difficulty managing steps and stairs.

- Difficulty in getting in and out of the car.

- Slipping or unbalanced on flooring.

- Lying down to eat.

Behavioural changes

- Reluctance to be groomed, petted or examined.

- Self-mutilation – nibbling over area of discomfort, constantly licking a joint.

- Anxiety/not settling at night/pacing/vocalising.

- Reluctance to interact with other dogs/people.

- A useful guide for owners to help think about and identify mobility problems and discomfort in dogs, which can also be applied to cats, is The 5 Principles of Pain (Canine Massage Guild), which is based on gait, posture, activities of daily living, behavioural changes and performance.

Caring for patients with poor mobility in the hospital setting

- Think flooring. Can dogs safely walk on the practice flooring without slipping? Do they have to negotiate steps to get in and out of the building, or into their kennel? The use of anti-slip flooring, rubber-backed mats and anti-slip tape cannot be overlooked. An inappropriate slide may result in a micro-trauma to an already arthritic joint, a strain to the superficial pectoral muscles or a sprain to the collateral ligaments of the carpus, all of which will result in an inflammatory and pain response.

- Orthopaedic mattresses and soft, comfortable bedding should be used to provide warmth, comfort, and protection of the joints – particularly in larger breeds.

- Both canine and feline patients with poor mobility should have raised food and water bowls to aid eating and drinking, preventing excessive weight transfer through the forelimbs – particularly if a forelimb pathology is identified.

- Patients that require clinical examinations, blood sampling or catheter placement on the floor should be on anti-slip mats to prevent the forelimbs from sliding. Yoga mats work very well for this, and can be easily rolled up and stored out of the way when not in use.

- Dogs with severe mobility issues should be aided as they move around the practice. A simple towel underneath the abdomen might be sufficient in those patients with a mild mobility issue. The use of a support harnesses is more suitable for patients with a more severe mobility issue (Figure 3).

- Informing members of the practice team that a patient has mobility issues can be achieved with a patient care card on the kennel door or by using “be nice I’m arthritic” bandanas (available at Canine Arthritis Management), which act as an instant visual to all practice staff to handle gently and carefully.

- Cats should be given low-sided, easily accessible litter trays that are large enough for them to move around in without tripping and losing their balance.

- Placing an anti-slip surface on cat scales should help prevent them slipping while being weighed.

- If possible, cats should be allowed and encouraged to move around the ward, and be provided with obstacles they can stand on. This will encourage weight bearing through the thoracic and pelvic limbs.

Mobility clinics

The RVN is perfectly placed to develop and run dedicated mobility clinics, and be a champion for advocating for patients with poor mobility (Figure 4).

By spending time with owners, the RVN can effectively educate them on all issues concerning mobility and the importance of appropriate exercise, activities of daily living (ADLs), weight management, nutritional supplementation and paraprofessional help.

The RVN can guide owners through the mobility journey and help them to be proactive rather than reactive.

While it is considered mobility is a problem of senior pets, recognising and educating owners that mobility starts at a young age is important. Many young dogs can have advanced OA, for example, due to developmental disease such as hip or elbow dysplasia, OCD, juvenile cruciate disease and luxating patellae. By picking up on these cases and diagnosing early, the client can be supported in making the right decisions to help slow down the progression of any disease state, thereby giving the patient the best chance at maintaining mobility for later in life.

Owners of healthy puppies and kittens should be advised on joint care and prevention of joint issues, and this can be done in nurse-led monthly “weigh and worm” clinics until the dog is six months of age, and then an “adolescent” clinic from six months of age. Such appointments are an ideal opportunity to open a discussion with the owner on joint and muscle health, such as exercise levels and types of exercise, playing with toys such as “chuck-its”, weight management and body condition, flooring, other potentially harmful habits, and appropriate neutering for joint care and skeletal development.

In the author’s experience, running dedicated mobility clinics for senior pets has always been met with a positive response from the client and, while some areas may be a challenge (such as convincing an owner of an overweight pet that losing weight will have a positive effect on mobility), they are generally well received, and recommendations are followed.

Nutraceuticals

The North American Veterinary Council has defined a nutraceutical as “a (non-drug) substance that is produced in a purified or extracted form, and administered orally to a patient to provide agents required for normal body structure and function, and administered with the intent of improving the health and well-being of animals”.

The nutraceutical industry is huge and unregulated. Nutraceuticals do not go through the rigorous safety and efficacy tests that drugs do and, as a result, many of the products that are on the market are mislabelled. That said, this places the RVN and veterinary team in the best position to be able to advise and guide their clients on the use of nutraceutical products, and helping them to make informed decisions with regards to active ingredients, what they do and how they may help.

The “ACCLAIM” criteria for choosing a nutraceutical should be advised where possible (Fox, 2017).

A – A name that you recognise? Products manufactured by an established company that provides veterinary educational materials.

C – Clinical experience. Companies that support clinical research/trials and have published data in peer reviewed journals.

C – Content. All ingredients should be clearly indicated on the product label.

L – Label claims. If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. Products with realistic label claims based on scientific studies, rather than testimonials, are more likely to be reputable. A product with a label with claims to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent a disease features illegal claims and should be avoided.

A – Administration recommendations. Dosing recommendations should be accurate and easy to follow. It should be easy to calculate the amount of active ingredient administered per dose per day.

I – Identification of Lot. A Lot identification number indicates a pre-market or post-market surveillance scheme exists to ensure product quality.

M – Manufacturer information. Basic company information should be clearly stated on the label and, ideally, this should include a link to their website or for contacting customer support.

The following is a list of active ingredients thought to contribute to joint health:

- Oil of green-lipped mussel.

- Glucosamine and chondroitin.

- Omega-3 fatty acids.

- Hyaluronic acid.

Laser therapy

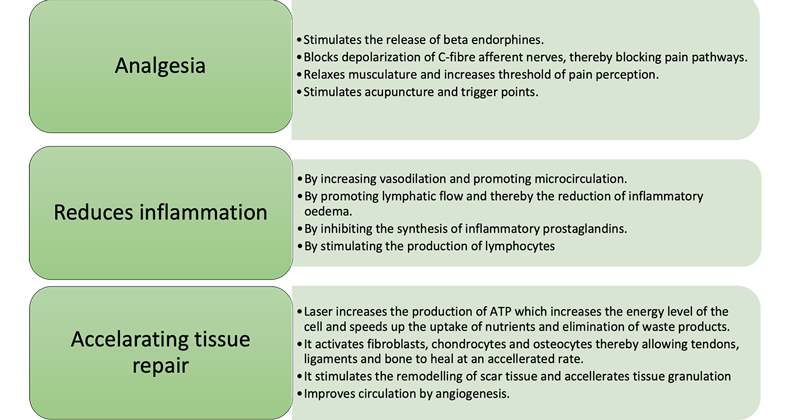

The use of photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT), or laser therapy, delivered with a therapeutic laser, is being increasingly used by pet owners and veterinary staff as an adjunct or alternative to standard medical therapies for the treatment of chronic painful conditions, such as OA and other musculoskeletal conditions.

PBMT can be used as a standalone therapy; however, when used as part of a multimodal approach for pain management and rehabilitation, the results are better appreciated.

The goals of laser therapy are to relieve symptoms such as pain and inflammation, and restore range of motion and function, thereby improving mobility and reducing the need for systemic medications, while improving overall quality of life. Veterinary practices that are fortunate enough to have a laser machine will see the benefits of improved mobility of their canine and feline patients.

When laser energy penetrates the tissues, the photons of light stimulate a physiological response at a cellular level. As the cells absorb the laser energy, an increase in the cellular respiratory and metabolic rates occurs. Many biological effects of laser therapy exist, which can be summarised in Figure 5 (Riegel and Godbold, 2017).

Clinical canine massage therapy

Clinical canine massage therapy utilises a combination of Swedish, deep tissue, sports, myofascial release, and the Lenton method to identify and treat musculoskeletal injury and disorders.

When a problem with mobility exists (lameness, postural changes, muscle weakness, myalgia, areas of overcompensation and so on), the formation of myofascial trigger points can occur.

A trigger point is a hyper-irritable band of focal point tension that is locally sensitive to pressure, can cause ischaemia to the tissues and refer symptoms of pain to other areas of the body (Muscolino, 2009).

Myofascial pain syndrome and wide-radiating myofascial pain occur when the myofascial trigger points activate and overstimulate the nociceptors, and inhibit mechanoreceptor activity.

Fascia is a highly sensitive, thin, cobweb-like tissue that surrounds all muscle fibres, muscles, nerves, tendons and ligaments, and allows these tissues to “slide and glide” smoothly, and without restrictions over one another.

When fascia becomes unhealthy, it becomes restricted, bound and stiff. Instead of it being a highly perceptive tissue, it becomes painful and can lead to hypersensitivity and allodynia.

These symptoms can result in stiffness, reluctance to go for walks or play, a reluctance to be petted, fasciculations along the spine, behavioural changes and so on.

A clinical canine massage therapist uses the art of palpation to perform a muscular health check, which can aid in the diagnosis and subsequent management of a patient with poor mobility. A systematic approach is used to palpate the muscle tissues and is guided by the four Ts: tone, texture, temperature and tenderness.

The effects of clinical canine massage can be profound and, in a recent clinical trial, 95 per cent of dogs responded positively to clinical canine massage (Riley et al, 2021). Improvement in mobility was seen due to the reduction of pain, improved range of motion of joints and improved proprioceptive awareness.

Many benefits to clinical canine massage exist, which include:

- Reducing muscle tension and inducing relaxation – especially in hypertonic muscles.

- Loosening up muscle fibres, reducing muscle spasms, and addressing trigger points and myofascial pain.

- Improving oxygen and nutrient supply to the muscles, and surrounding tissues

- Improving circulation to the tissues resulting in an increase in tissue temperature and elasticity, and therefore, accelerated muscle recovery (Bockstahler et al, 2014). An increase in temperature also improves viscosity of the synovial fluid within the joint, which allows the joint to move more freely.

- Removal of allogenic substances from the muscles, such as irritants produced during inflammation and waste products such as lactic acid and free radicals (Bockstahler et al, 2014).

- To mobilise and break down adhesions in the fascia and muscles.

- To control pain via the pain gate, removal of noxious chemicals and the release of endorphins.

ADLs

The veterinary team can go a long way to helping to improve a patient’s mobility within the practice environment through education and advice given in the mobility clinic, and with the use of modalities such as laser, massage, nutraceuticals and so on.

However, this will be of little or no benefit to the patient if the owner fails to address problems within the home environment, which contribute to the cause of the mobility problem; for example, the arthritic dog that must negotiate steps or laminate flooring will continue to cause microtraumas to the cartilage if it stumbles, or slips resulting in further inflammation and pain. Panel 1 lists the various things owners can adjust with their pets’ ADLs to aid recovery, prevent re-injury or deterioration in conditions that result in poor mobility.

Panel 1. Adjustments owners can make to aid poor mobility

- Raise food and water bowls.

- Consider using stair gates to deter pets from going up and down stairs.

- Provide steps to prevent pets jumping on and off furniture.

- Make sure beds are easy to get in and out of, and large enough to stretch out on. Memory foam should be considered.

- When exercising, use a collar or harness, and consider the length of the walk, terrain and pace.

- When playing, avoid “chuck-it” and “tug-o-war”-type games. Find alternative ways to play, such as rolling a ball, and mind stimulation games.

- Provide steps for when getting in and out of a car.

- Avoid wet and cold weather. Use a coat.

- Avoid tiles, laminate and wooden flooring – use anti-slip mats, rugs and tape.

Conclusion

It is important the whole practice team works together to recognise and manage mobility concerns with patients. Once recognised, an appropriate care plan can be developed and implemented using a multimodal approach, and the skills of the RVN and other paraprofessionals.

- Reviewed by Nicci Meadows, BVetMed, CertAVP, GSAS, MRCVS

Leave a Reply