Feline aortic thromboembolism (FATE) is a medical emergency that is commonly encountered in veterinary practice.

It is caused by the formation of a thrombus within the cardiac chambers (often the left atrium), which then embolises and blocks the flow of blood. Clinical signs will vary depending on which vessel is affected, but sadly the outcome is often poor. However, with prompt and accurate treatment, patients can have a better prognosis.

What is FATE?

FATE is a condition that occurs when a thrombus forms in the heart and then travels through the arteries until it becomes lodged in a smaller vessel. The aorta and iliac arteries are commonly affected, resulting in reduced or absent blood flow to the hindlimbs.

In the cat, the external iliac arteries bifurcate from the abdominal aorta first forming a Y, and then the internal iliac arteries arise (trifurcation). The external iliac arteries give origin to the femoral arteries.

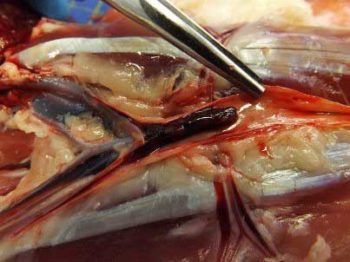

A recent study reported the trifurcation of the aorta (Figure 1) is the most common localisation in cats affected by FATE, representing 90% of cases (Eberlé et al, 2022). For this reason, the majority of cats will show hindlimb paresis/plegia with acute pain and lameness in the absence of a traumatic event.

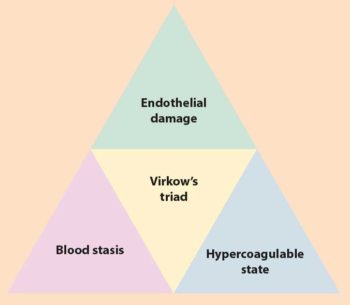

The formation of a thrombus is a result of Virchow’s triad (Figure 2), which consists of stasis of blood flow, endothelial injury and hypercoagulability. Any underlying condition that leads to alteration of these three factors can contribute to the formation of a thrombus and increase the risk of FATE. Some of the most common underlying conditions include cardiomyopathy, hyperthyroidism and chronic renal disease.

Cardiomyopathies, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), can lead to left atrial enlargement and poor atrial systolic function. Left atrial enlargement can also result in endothelial exposure. These factors are associated with reduced blood flow velocity, and can initially be observed as spontaneous echocontrast (smoke) on echocardiography and then thrombus formation.

A recent study demonstrated endothelial damage in cats with remodelled left atrium, and suggests that expression of endocardial von Willebrand’s factor may be increased, and serve as a pro-thrombotic substrate, potentially playing a role in the development of FATE in cats with underlying cardiomyopathy and left atrial enlargement (Cheng et al, 2021).

What cats are usually affected and what are the clinical signs?

FATE can occur in cats of any age, breed or gender, but it is most commonly seen in middle-aged to older cats with underlying heart disease.

In a study on 29 cases of FATE, 28 had underlying cardiomyopathy as a cause of the thromboembolic event (Eberlé et al, 2022). Non-pedigree cats are most commonly affected, followed by Siamese, British shorthair, Burmese and Persian (Borgeat et al, 2014). Generally, it is reasonable to consider breeds predisposed to HCM to be at risk of FATE. Male cats are also over-represented (Eberlé et al, 2022). Other conditions that have been associated with FATE are pulmonary and hepatic carcinomas.

Cats with FATE typically present acutely. Clinical signs classically include sudden onset hind limb paralysis, pain and lameness.

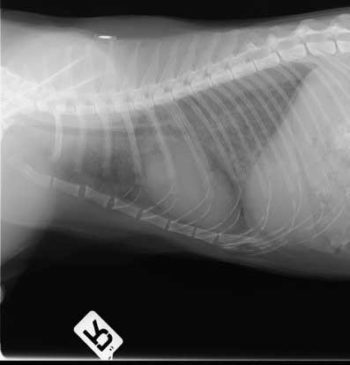

Some cats that suffer from FATE can present with signs of congestive heart failure (CHF) secondary to cardiomyopathy. CHF can cause dyspnoea that is caused by pulmonary oedema, pleural effusion or a combination of both. However, readers should note that only 60% of cases present with FATE and concurrent CHF. Otherwise, tachypnoea is usually pain related.

It is important to exclude traumatic events as a possible cause of the above signs by collecting an accurate history and checking for wounds. Commonly mistaken differentials may include spinal cord disease (neoplasia, fibrocartilagenous emboli or trauma), intracranial disease or polyneuropathies; however, these conditions are usually associated with other neurological deficits or spinal pain (whereas FATE involves pain of the affected limb[s] only).

Neoplastic conditions are usually more chronic in their presentation. Other clinical signs may include a decreased or absent femoral pulse, tachypnoea, cold and pale hindlimbs (Figures 3a and 3b) and vocalisation. In severe cases, cats may also exhibit signs of shock such as hypothermia, tachycardia, hypotension and dyspnea.

It is important to note some cats may show signs of heart disease prior to the development of FATE, such as lethargy and exercise intolerance, and these could be highlighted with the collection of clinical history once the patient is stable. In fact, in one study approximately half of the cats with FATE were dyspnoeic and/or had an auscultation abnormality (arrhythmia or gallop sound, for example) on presentation (Borgeat et al, 2014).

Although rare, some cats could develop FATE in other vascular regions other than the aortic trifurcation. Less than 10% of cats were reported to have either the right or left forelimb affected in a study on 250 cats affected by FATE (Borgeat et al, 2014).

Embolisation to other organs is also possible – such as mesenteric arteries, kidneys or the brain – leading to different clinical signs, but reliable data regarding clinical signs and prevalence associated with cerebral or renal thromboembolic events are lacking.

How do we diagnose FATE?

As FATE is usually cardiac in origin, it is important for clinicians to recognise and diagnose signs of CHF, and determine that the heart is the origin.

One option is to perform a thoracic point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) examination. This can be used quickly and efficiently in patients suspected to be suffering from cardiac disease. They are simple to perform consciously, non-invasive and relatively stress free for the patient.

By placing an ultrasound probe between rib spaces and observing for the presence of B-lines (vertically orientated, bright lines from the pleural surface extending the length of the entire image) a clinician can diagnose “wet lung” tissue caused by interstitial or alveolar infiltrate that, alongside other clinical signs, increases the likelihood that the patient is suffering from CHF (Lisciandro et al, 2017).

A POCUS might also reveal pleural effusion associated with CHF. Another method of confirming CHF is via radiography. Both dorsoventral and lateral views can be used to assess the pulmonary vasculature. Typically, on thoracic radiographs cats with cardiogenic pulmonary oedema show interstitial to alveolar pulmonary opacities, pulmonary vascular enlargement and cardiomegaly (Figure 4).

The downside of radiography is that it often requires sedation or general anaesthesia to reduce the likelihood of movement artefacts. In emergency situations this is not ideal.

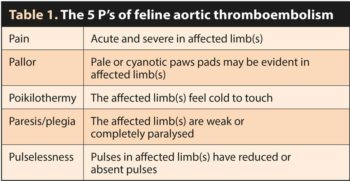

Diagnosis of FATE is usually made on the presence of the aforementioned clinical signs; however, further tests and imaging modalities can provide information to confirm FATE and its underlying cause. Suggestive clinical findings of FATE are often referred to as the “5 P’s” (Table 1).

Motor function may or may not be present in the affected limb(s).In some cases, thromboembolism can be identified using ultrasonography. When visualised within the artery, either full or partial occlusion of the vessel may be observed. Colour Doppler may be used supplementary to this to confirm hypoperfusion, or in some cases complete lack of blood flow. On ultrasound, the thrombus is often isoechoic to the surrounding tissues, making the diagnosis more challenging. Limitations of ultrasonography include operator skill and the position of the thrombus; more proximal emboli may not be possible to find.

Blood work may aid the clinician in diagnosing FATE. Generalised hyperglycaemia related to stress is commonly seen in patients with aortic thromboembolism. Blood samples taken from an affected versus non-affected limb will show reduced glucose and increased lactate due to hypoperfusion in the affected limb(s).

Lack of blood flow also increases levels of muscle enzymes creatinine kinase and aspartate aminotransferase, which may be seen on serum biochemistry. Hyperkalaemia may be identified with reperfusion injuries and azotaemia may transpire secondary to dehydration or obstruction of renal arteries in some cats.

In rare cases where an infrared camera is available, heat mapping may allow the clinician to visually observe hypoperfused limbs due to a reduction in temperature. Although this method is not routinely available, its speed and non-invasiveness is advantageous, and may be of use in the future (Pouzot-Nevoret et al, 2017).

What risk factors are associated with FATE development on echocardiography?

Echocardiography can be a useful tool in determining cats that are at risk of an aortic thromboembolism.

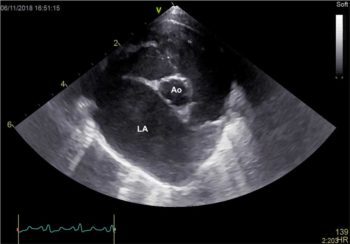

Enlargement of the left atrium, secondary to myocardial diseases (most commonly HCM) or incompetence of the mitral valve leads to blood turbulence, stasis and, therefore, thrombus and emboli formation. Severe left atrial dilation may be seen subjectively on echocardiography (Figure 5); however, the left atrial to aortic diameter ratio (LA:Ao) can be measured from the right parasternal short axis view at the level of the heart base. In cats, an LA:Ao ratio of greater than 1.5 (Abbott and MacLean, 2006) suggests enlargement of the chamber.

Another method of evaluating left atrial size is from the right parasternal four chamber view optimised for the atria and calculating the diameter of the left chamber from the interatrial septum to the free wall, parallel to the mitral annulus. The normal measurement for the cat is less than 16mm. Evidence of thrombi may be visualised in the left atrial appendage as hyperechoic, often rounded structures, either adherent to the walls or moving freely in the chamber (Figure 6). The presence of spontaneous echocontrast or “smoke” indicates increased coagulability and a higher risk of clot formation.

Other echocardiographic measurements such as reduced left atrial fractional shortening (a measure of atrial systolic function) and reduced left atrial appendage blood velocities, using Doppler echocardiography, have also been linked with myocardial disease and CHF – and, therefore, predispose cats to thromboembolic events (Schober and Maerz, 2006; Linney et al, 2014).

How do we manage FATE?

Emergency management

Initially, these cats present acutely painful and are often tachypnoeic or dyspnoeic; therefore, the first line of management is to provide analgesia and supplemental oxygen.

Methadone is the analgesic of choice, being a full u-receptor agonist. In the absence of methadone, buprenorphine may also be used. NSAIDs should be avoided, at least until the clinician has knowledge of blood pressure and renal function. IV access should be secured, provided this doesn’t cause unnecessary stress for the cat.

It is important to stabilise the cat as much as possible before overly stressing it as this can worsen CHF or even lead to sudden death.

In some instances, euthanasia is recommended before further diagnostics or treatment. This decision is governed by many things including owner, clinician and patient factors. If treatment is opted for, a minimum of 72 hours is often needed to see significant changes in paralysis/paresis.

Following analgesia, assessment for CHF should be pursued and also to confirm that the heart is the source of the embolus. As mentioned earlier, approximately 60% of cases will have CHF and so require diuresis. Thoracic point-of-care ultrasound should be used to look for evidence of pulmonary oedema and/or pleural effusion, together with a dilated left atrium (Figure 5).

Alternatively, thoracic radiography can be performed, but this has fallen out of favour when compared to ultrasound in the emergency setting. If CHF is confirmed, or a high level of suspicion exists then an initial bolus of 2mg/kg furosemide should be given intramuscularly or intravenously. This should then be followed by intermittent boluses of 1mg/kg until the cat is more stable, at time intervals determined by several factors including hydration status, respiratory compromise and renal function.

Thoracocentesis is needed for those cats with significant volume pleural effusion.

Short-term management

After stabilisation, the key to therapeutic management is antithrombotic and antiplatelet therapy. In one study, cats that did not receive clopidogrel and/or aspirin were more likely to be euthanised or die within 7 days (Borgeat et al, 2014). The use of antithrombotics does not result in clot lysis – instead they prevent further clot formation.

Low molecular weight heparin, such as dalteparin at 80IU/kg to 150IU/kg every six to eight hours SC, or unfractionated heparin at 250IU/kg to 300IU/kg every eight hours SC can be initiated if the cat cannot tolerate oral medication. Indeed, these drugs are often used in combination with antiplatelet treatment for the first two or three days of hospitalisation.

As soon as oral medication can be tolerated then clopidogrel should be started. Clopidogrel is the initial antiplatelet drug of choice due to evidence that it is superior to aspirin in preventing recurrent FATE episodes (Hogan et al, 2015). An initial loading dose of 75mg/cat by mouth, followed by a maintenance dose of 18.75mg/ cat by mouth once daily, is often used.

Clopidogrel is bitter and might cause hypersalivation or hyporexia in some cases. It is possible to place the tablet in a gelatin capsule, and a liquid formulation is also available. Aspirin can be given concurrently (or as an alternative in cats that don’t tolerate clopidogrel).

However, no evidence exists that dual therapy is more efficacious than single therapy and aspirin carries a higher risk of side effects, including gastrointestinal ulceration.

A further alternative to clopidogrel and aspirin is the factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban (2.5mg/cat by mouth once daily). This drug can be used alone or in combination with clopidogrel. No data exists to support its use, but in people factor Xa inhibitors are being used more frequently than warfarin in the prevention of strokes associated with atrial fibrillation, for example, due to its higher safety profile (Patel et al, 2011).

The use of a thrombolytic, such as tissue plasminogen activator, has gone out of favour in recent years, with studies showing no significant survival benefit of its use, although studies are relatively underpowered (Guillaumin et al, 2022).

Other aspects of care while hospitalised include the maintenance of analgesia, at least until the cat is more comfortable, which usually happens after the first 48 hours. As soon as the cat is more comfortable physiotherapy can be initiated, using passive range of motion and massage.

Monitoring for complications is also important – particularly reperfusion injury, which results in hyperkalaemia and acidosis. Monitoring of heart rate and respiratory rate is key, together with renal function and electrolytes. Bloods are usually checked at least once daily for the first 48 to 72 hours after presentation or more frequently if clinical signs necessitate it. Successful management of reperfusion injury in these cats provides a significant challenge.

Long-term management

Antiplatelet medication should be continued indefinitely, and in most cases clopidogrel is the drug of choice.

The decision on whether to discharge a cat with single or dual therapy is based on the cat, client and echocardiographic findings. For example, if a cat is relatively easy to medicate and has a large thrombus within the left atrial appendage then dual therapy is rational. If a cat is not easy to medicate then single therapy should be tried initially.

As previously mentioned, we have no recent data to suggest whether dual therapy is more efficacious at preventing recurrence than single therapy, although there is one study showing that it is well tolerated (Lo et al, 2022).

Those cats that have underlying cardiac disease as a cause of their FATE may require ongoing CHF management and further investigations of their underlying cardiac disease.

Gold-standard assessment is with Doppler echocardiography, which should only be performed in a stable patient.

Management of CHF is beyond the scope of this article and readers are directed elsewhere for this information.

Physiotherapy should be continued for several weeks after discharge until motor function improves.

It will be important to initially evaluate the patient frequently for complications such as necrosis of affected limbs, development of heart failure and so on.

What is the prognosis for cats affected by FATE?

The long-term prognosis for these cats is guarded to poor – especially if CHF is present. Cats with bilateral hindlimb paralysis have a significantly poorer prognosis than those cats with unilateral disease or paresis.

In general, bilateral disease is associated with a 30% to 40% survival rate and unilateral disease with 70% to 80%. Negative prognostic indicators include the presence of gallop sounds, rectal temperature less than 37°C, bradycardia, previous FATE episode and having two or more limbs affected.

In general, clinical signs will start to improve over the first 24 to 48 hours, with many of those cats surviving this time period regaining most or all of the motor function within one to two months. Long-term complications may result as a consequence of FATE, including muscle contracture, skin necrosis and sloughing and persistent neurological deficits resulting in excoriation of the paws.

Can we prevent the disease?

Unfortunately, complete prevention of FATE is not possible. In cats that received clopidogrel, the median time to recurrence of a FATE episode or cardiac death was 346 days versus 128 days for cats on aspirin alone (Hogan et al, 2015). This suggests that although it is not possible to wholly eliminate the chances of FATE, the use of anti-platelet medication such as clopidogrel can reduce the likelihood of an event occurring.

Other anti-thrombotic drugs such as rivaroxaban have been tolerated well clinically in trials; however, long-term data concerning their use and effectiveness in controlling or preventing FATE is lacking. Cats with heart murmurs or known heart conditions would benefit from regular assessment by a cardiologist to track progression of their condition.

Anti-platelet therapy should be considered in cats showing signs of CHF or in those with stage B2 disease with smoke or left atrium enlargement. It is important to make owners aware that cats receiving treatment are still susceptible to thromboembolic events and sudden death.

- Some drugs mentioned in this article are used under the cascade.

Leave a Reply