Background: The concept of tailoring parasite treatment for individual animals according to their circumstances and specific risk factors – the so‑called “risk‑based parasite control approach” – has gained a momentum in recent years. Key advisory and regulatory bodies have provided position statements in favour of the use of risk‑based parasite control.

Despite this enthusiasm, challenges exist to the integration of this new treatment model into clinical practice. Insufficient evidence exists to support – or doubt – the efficacy of a risk‑based approach as many questions remain unanswered, and the factors affecting animal susceptibility to infection, treatment responses and adherence to treatments are not fully defined. This is further complicated by the dynamic nature of parasite risk.

Methods: This cross-sectional study used a survey to investigate perception of small animal clinicians towards implementing a risk assessment-based approach to parasite control.

Results: Of the 119 participants who completed the survey, 81% (n = 97) agreed that individually tailored parasite treatment is the best compromise to minimise environmental contamination while still preventing parasite infestation.

A total of 86.5% (n = 103) would like to see more research conducted into veterinary medicine‑related parasiticide products in the environment, including levels, extent of harm and pathways into it.

The results also showed a need for longer consult times, and more resources to assist clinicians in decision making on individually tailored parasite control would be helpful. Limited autonomy was a major limiting factor for adopting risk-based parasite control for many veterinarians. The study highlighted the need for more educational content and improved risk-benefit assessments to veterinary professionals and the public.

Conclusions: The results showed that the environmental impact of parasiticides is well recognised and an appreciation exists that more work needs to be done. Although the study findings captured clinicians’ motivation, a sizeable fraction indicated scepticism in the risk-based approach’s ability to meet the required expectations, and in the readiness.

In part one of this series, the authors began to share their insights into the attitude of small animal vets towards a risk assessment-based approach to preventive parasite control.

Their cross-sectional study, receiving responses from 119 participants across the UK, initially considered perceptions around environmental concerns, and the efficiency and treatment outcomes of a risk assessment-based approach.

Enthusiasm about role vets play in protecting environment

As anticipated, enthusiasm was shared about the role of veterinarians in protecting the environment. However, participants noted that many challenges – including a lack of autonomy in practice and owners using non-prescription medication – would prevent them from fully realising this. Meanwhile, participants strongly agreed (75%; n = 89) that individually tailored parasite treatment will minimise the risk of parasiticide resistance, although many participants challenged the idea that a risk-based approach can offer a better efficacy than the blanket approach. Part two, the last in this series, considers topics including cost and consult time.

Questionnaire statements were designed to gain more insight into the perception of the participants on the effect of practice policy, delivery of health services, role of vets, role of pet owners, available resources and financial implications on the adoption of an individually tailored parasite control approach.

Risk assessment-based parasite control and cost effectiveness

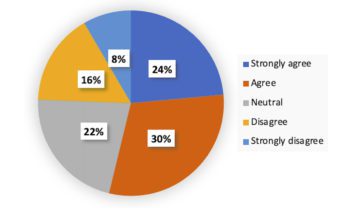

The participants’ response to the statement, “Individually tailored parasite treatment will be the most cost-effective option for owners” revealed that the number of participants who are unsure (neutral) was equivalent to the number of those who strongly agreed and agreed combined.

Only 18.6% (n = 21) and 1.7% (n = 2) disagreed or strongly disagreed, respectively (Figure 1a). The lack of enthusiasm may reflect the participants’ concerns about the potential for undermining one’s professionalism and the industry influence: “I think we are trained in defensive medicine and the fear of a patient suffering from what around us are rarely diagnosed diseases like lungworm and Lyme disease, leading to massive overuse of parasiticides. The big pharma companies have worked strongly to promote these anxieties.”

Practice income and monthly plans

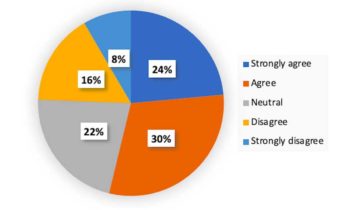

The participants’ response to the statement “My practice relies on the income received from monthly plans that include parasite control” revealed that 24% (n = 28) and 30% (n = 36) strongly agreed or agreed, respectively (Figure 1b). On the other hand, 16% (n = 19) and 8% (n = 10) disagreed or strongly disagreed, respectively. The neutral responses were 22% (n = 26).

Some respondents expressed scepticism over the power of their voice to change current practice policy, questioning the willingness of practice owners to replace the conventional monthly plans with a less-lucrative approach. One participant noted: “The major disadvantage of individually tailored treatment is that most practices keep the costs of their parasiticides down by ordering only one or two products in bulk. If a greater variety of products is needed then they may be more costly to owners.”

Another participant commented: “Monthly plans are the enemy of risk-based assessment and my main barrier to using it. As otherwise they are generally a good thing for owner, practice and pet, a way of incorporating risk-based assessment into them would solve a lot of problems.”

Financial adaptation and risk assessment based parasite control

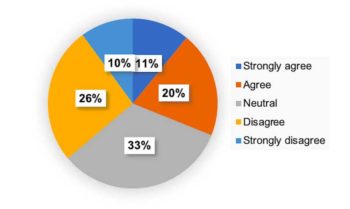

The participants’ response to the statement, “Companion animal vet practices will need to find alternative sources of income in order to adopt individually tailored parasite control approaches” revealed that the majority disagreed (26%; n = 31) or strongly disagreed (10%, n =12).

Those who were neutral were 33% (n = 39). Additionally, 20% (n = 24) and 11% (n = 13) agreed or strongly agreed, respectively (Figure 1c). One participant noted: “I think clients broadly fall into a worming every three months category, or not at all. I also think that moving away from a one-plan-fits-all mentality is going to be pretty difficult.”

Consult time and risk assessment-based parasite control

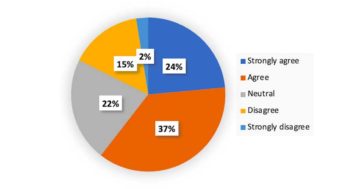

Most of the participants strongly agreed (24%; n = 28) or agreed (37%; n = 44) with the statement “Vets will need longer consult times to conduct a risk assessment to individually tailor parasite control” (Figure 1d).

Some participants were concerned about the feasibility of the implementation process due to the need for more consult times: “If individual parasite consults were a thing, while that would increase workload at the moment, when the industry is less stretched, that would be a good idea.

“Nurses are good at parasite consults, but again, there’s far too few in my practice at the moment to utilise that.”

Others felt overwhelmed at the prospect of engaging with an additional initiative that required more work: “Difficult to manage this properly without extra time – and, therefore, more money for client?”

Resources and risk assessment-based parasite control

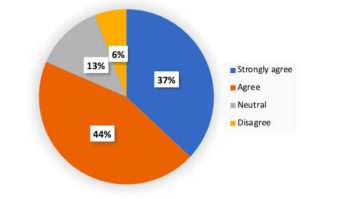

Most of the participants strongly agreed (37%; n = 44) or agreed (44%; n = 53) with the statement “I would find a resource that assists me in decision making for individually tailored parasite control helpful” (Figure 1e).

Some responses indicated the need for training veterinarians. Some representative comments included: “A website that can be used for any vet, registered veterinary nurse, student veterinary nurse or suitably qualified person/receptionist to determine the best drug(s) for a patient would be amazing.”

Equally, some responses indicated the need for training the clients.

Some representative comments included: “I think mixed messages will be very difficult for clients to understand and we may not know if, for example, a client has changed to raw feeding.”

“Pressure exists from some clients for maximum preventive treatment; client education is an important factor in treatment choice and requires time to discuss.”

“Owners often do not understand parasitic resistance, and I think this is something that will become problematic in the future and needs to be addressed now.”

Poor compliance of clients was repeatedly highlighted by some clinicians. For example: “Owner compliance is already very poor. Less than one-third of recommended products are actually given.”

“Client compliance for preventive treatments is very poor. Would be more useful if certain outlets stop selling ineffective products.”

“Worried that owner compliance will decrease with individual plans – ‘my friend uses this, x amount of times’ – or similar.”

“I think compliance would be poorer, as clients would just not provide the products and lose track of time, rather than when they can put it on their calendar to give regularly, so pets would be less well treated.”

Some indicated the possibility of client resistance to the use of this approach due to mixed messages: “If there will be an owner awareness campaign, all vets will be bombarded with people that misunderstand what you are trying to teach them, then they will be claiming that we are trying to scam them. Cheap and available at [superstores] is what they want.” Or lack of confidence: “Some owners are already aware; for example, doing faecal egg counts rather than regular worming (not necessarily effective).”

Discussion

The use of blanket treatment is coming under increasing scrutiny, in part because of growing recognition of the flaws of the one-size-fits-all approach. Therefore, the search for the best practice in parasite control has intensified over the past few years.

This quest corroborates well with the greener veterinary practice initiative led by the BVA to promote parasiticide stewardship and evidence-based use of parasiticides. As a consequence, the idea of providing preventive parasite control based on individual needs has come to light and gained a momentum. This momentum has been accompanied by many questions regarding the feasibility of the approach and the readiness of the profession to adopt it. For example, incorrect application of the risk-based approach can lead to increased zoonotic infections, animal health and welfare compromise, and potentially drug resistance.

To identify barriers and enablers to implementation of risk assessment-based parasite control approach, the present survey was conducted to examine small animal clinicians’ perception of this approach. Although the small sample size of the study participants, together with the convenience sampling approach, may limit the generalisability of the study findings, the responses obtained in this survey suggest the complexity and uncertainty surrounding this issue, and indication for further investigation and clarification.

In the first part of the study, we investigated veterinarians’ perception of whether risk assessment-based parasite control can alleviate the environmental concerns about the use of companion animal parasiticides.

Analysis of the survey data showed significant interest in protecting the environment. This should come as no surprise, given the increasing concerns about spot-on ectoparasiticides contaminating the natural environment, via pets entering water bodies, bathing, washing of pet bedding, hands or other surfaces that come into contact with treated animals, as well as run-off from closed surfaces and their potential adverse impact on ecosystems and public health1.

The same routes of water contamination could happen with collars. Further pathways for contamination unaccounted for include oral formulations (for example, from excretion via urine and faeces), in addition to manufacturing, storage, as well as disposal of unused medicines, containers and faeces2.

Striking a balance between effective parasite control and avoiding environmental contamination can be achieved by educating pet owners on the correct application of products, responsible disposal of packaging, and avoiding swimming and shampooing after topical applications, which will help reduce the environmental impact of parasiticides3.

Additionally, the wide availability and accessibility of authorised veterinary medicine – general sales list products, popularity of products on mail order schemes or repeat prescriptions, and poor owner compliance are some of the challenges that must be tackled.

Given the growing concerns of environmental contamination caused by frequent use of parasiticides, more efforts should go into field studies to assess the real impact and level of environmental fate and potential toxicity of most ectoparasiticides4-5.

The survey showed that participants were sceptical of the ability of risk-based parasite control approach to address these concerns, partly due to factors beyond the control of the veterinarians. Most of the clinicians, however, highlighted the need for more support for pet owner via awareness campaigns for parasite control, drugs and environmental concerns.

Owner education is essential to compliance, where understanding about why and how best to give treatment improves the likelihood of following instructions6. Some of the strategies that can maximise compliance include client education, maintaining good communication, fostering trusting relationships, and consideration of owner preferences, expectation and circumstances7-9.

However, educational campaigns need to be carefully designed to avoid enabling pet owners to influence treatment decisions, or to take matters into their own hands and not give appropriate or any parasite control, or not involving veterinary professionals in the treatment plan of their pets.

Additionally, pet owner education campaigns need to be careful to not dissuade individuals from veterinary medicines as a result of their potential side effects, to send them towards alternatives or not use them at all.

Therefore, increasing pet owner education and involvement in parasite control decisions will likely result in greater appreciation of the important role of parasiticides in protecting animal health, and in understanding the potential environmental impact of applications of these parasiticides if used inappropriately.

The second and third survey topics sought to examine if the veterinarians felt that a risk-based approach could improve treatment outcome and whether it will impose extra demands from the clients, veterinarians and practices. Only 40% think that individually tailored parasite treatment will be the most cost-effective option for pet owners.

The veterinarians’ response highlighted the reliance of the practices on the income obtained from the monthly plans, and the potential strain adopting the new parasite control approach would put on income sources and consult times.

Some practices may only stock certain types of products or have strict policies about timings for parasite control. If these practices opt to incorporate risk-based control into monthly plans, then logically, additional costs need to be absorbed by practices, not clients to help improve compliance.

Wright argues that flexible practice health plans offering affordable routine parasite screening and risk assessment-based parasite prophylactic treatments can reduce the excessive use of parasiticides, and increase compliance10.

Interestingly, a strong agreement was noted regarding the need for resources to assist in decision making for individually tailored parasite control. This finding suggests that veterinarians are conscious of the opportunities and challenges associated with a risk-based treatment approach. However, they struggle to capitalise on these opportunities or to tackle the challenges because of how parasite control is currently implemented in clinical practice.

The survey revealed that veterinarians lack sufficient autonomy to prescribe off licence. A risk exists of veterinarians being vulnerable if prescribing off the data sheet, so it is important to make sure datasheets account for appropriate risk, and these are kept up-to-date with updating risk factors.

The survey results also point to the veterinarian’s lack of knowledge about active ingredients. It seems that veterinary professionals will need more continuing and responsive education in parasite epidemiology, risk factors, disease, current products and active ingredients, as well as improved support and mentorship from experienced clinicians who are more knowledgeable in this new approach.

Communication approaches or tools that connect veterinary professionals with their clients can improve compliance and patient care.

Veterinary nurses may be better placed to assist with the risk-based approach. With an average vet consult time of 10 minutes11, time is limited to discuss and devise an individualised treatment protocol, in addition to other tasks involved in a vet consultation.

The knowledge and skills of veterinary nurses allow them to handle parasite control plans, and they have the potential to play a vital role by leading parasite prevention clinics6,12-15. Equally so, having a pre-consult risk assessment survey to fill out, such as Parassess and MyPet Persona, could aid in sifting through risk and save time, so veterinarians have to only pick the appropriate product.

Conclusion

The most effective way to implement an individually tailored parasite control approach remains to be defined.

The survey results contribute new understanding of UK-based small animal clinicians’ perception of a risk-based parasite control approach and reasons for or against, as well as complicating factors to following this approach.

The results also showed that a need exists for longer consult times and more resources to assist clinicians in decisions for making individually tailored parasite control helpful.

The study highlighted the need for more educational content and improved risk-benefit assessments to veterinary professionals and the public. Evidence to support the efficacy of risk-based approach is insufficient, as many questions are still unanswered.

The threat also exists that if the risk-appropriate treatment is not followed properly, this could have immediate deleterious effects on animal health and welfare (for example, resulting flea allergic dermatitis or lungworm infection). More research investigating risk-based parasite control approach efficacy is crucial to helping assess this uncertainty.

This will enable new clinical guidelines supporting the approach to be derived from both theoretical and applied research, increasing the likelihood of success.

- The authors declare they have no competing interests.

- The authors would like to thank all study participants.

Leave a Reply