A nine-year-old male Rottweiler presented to the referring veterinarian with a one-week history of lethargy and inappetence.

Clinical examination and abdominal ultrasound demonstrated the presence of abdominal effusion, which was drained for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, and submitted to an external laboratory for analysis.

Haematology examination revealed moderate leucocytosis (26×109/L), but blood smear examination was not performed. Minimal changes – likely clinically not significant – were seen on biochemistry.

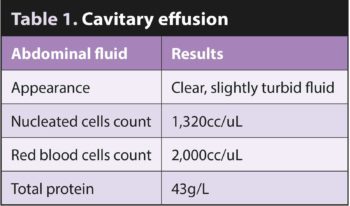

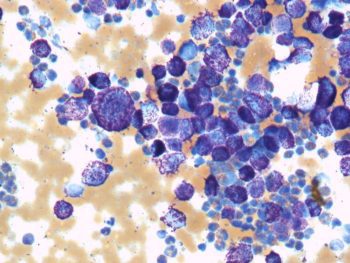

The fluid appeared poorly cellular with high protein content (Table 1). A concentrated preparation obtained from the submitted fluid was examined (Figure 1). The background was clear with moderate numbers of red blood cells. Frequent leukocytes were present – mostly eosinophils (approximately 70%), characterised by the presence of typical round orange intracytoplasmic granules (orange arrows). Lower percentages of small lymphocytes (blue arrows), macrophages and segmented neutrophils (black arrows) were also present.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of eosinophilic effusion was made.

Follow-up

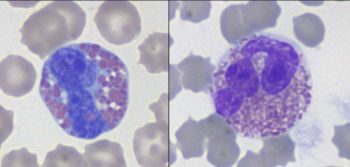

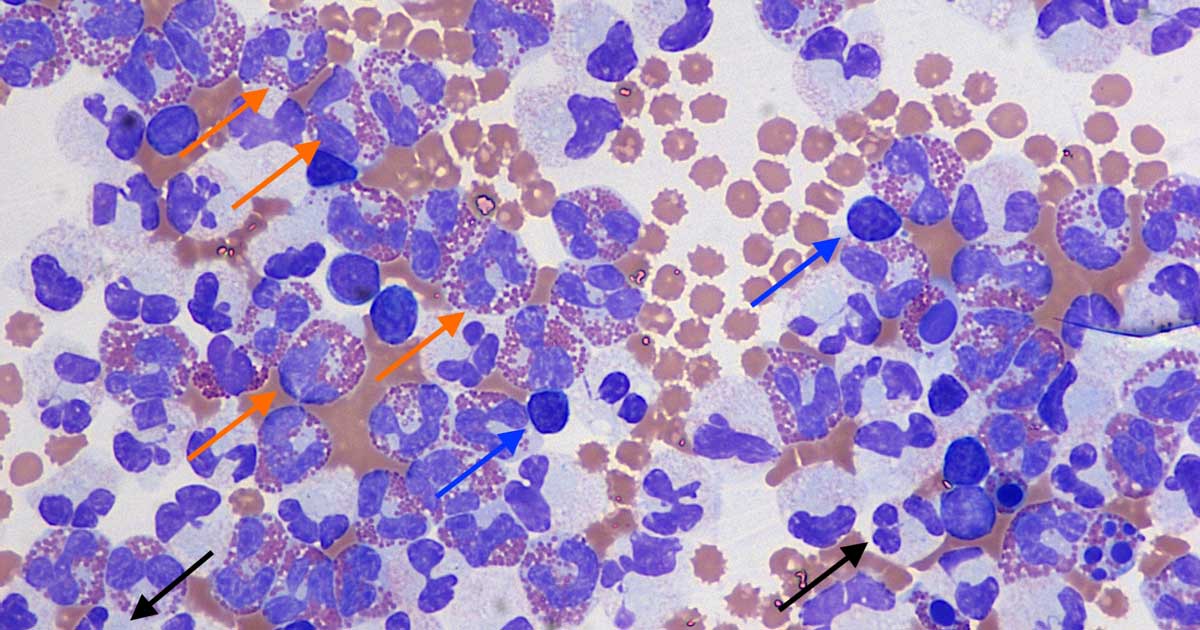

Abdominal ultrasound was repeated after the fluid was drained. The liver and spleen were diffusely hyperechoic, but did not show distinct masses. Fine-needle aspirates were taken from both organs and showed increased numbers of granulated mast cells with some signs of atypia (anisocytosis/anisokaryosis – cell/nuclear size variation), and often forming aggregates (Figure 2).

These cytology findings were supportive of mast cell tumour. Haematology was repeated and blood smear examination revealed occasional granulated mast cells. Visceral mast cell tumour was considered the likely cause for this eosinophilic abdominal effusion and for the mastocytaemia.

Visceral mast cell tumours are uncommon in dogs, and often involve primarily the spleen, liver and/or gastrointestinal tract. The prognosis is overall poor. Over the following week, the dog deteriorated; the owners declined further treatment and the dog was euthanised.

Insight

Eosinophilic peritoneal effusions are very uncommon in dogs and associated mainly with malignancy, in particular lymphoma and visceral mast cell tumour.

Selected infectious agents may also cause eosinophilic effusions – in particular fungi and parasites (for example, peritoneal cestodiasis, sarcocystosis). Other very rare causes that have been reported in the literature include liver lobe torsion and intestinal lymphangiectasia.

Take-home message

Cytology is crucial for the interpretation of cavitary effusions, and diagnosis should not rely on total cell count and fluid protein only. Based on these data only, for example, this effusion could have been wrongly interpreted as a traditional protein-rich transudate (formerly known as modified transudate).

On the contrary, it was mainly composed of eosinophils suggesting a specific list of differential diagnoses.

Leave a Reply