The synergy between evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM) and quality improvement (QI) provides practices with the perfect opportunity to make the most of the growing evidence base.

EBVM aims to make the clinical decision-making process easier by combining the veterinary professional’s expertise and judgement with the most relevant and best available scientific evidence, as well as patient circumstances and owner values.

This approach has had significant impact in veterinary care over recent decades, as demonstrated by the case studies published by RCVS Knowledge and Sense about Science in Evidence-Based Veterinary Medicine Matters, a landmark document bringing together 15 key veterinary organisations to affirm their commitment to veterinary medicine based on scientific principles.

As the publication shows, EBVM has been at the heart of the eradication of the cattle disease rinderpest; successful strategies to prevent bird flu; the rapid and accurate diagnosis of colic, one of the most common causes of death in horses; new techniques to treat bulldogs with breathing problems; new methods to reduce seizures in dogs with epilepsy; faster means of detecting antimicrobial resistance; and many other invaluable advances.

Quality improvement

QI owes its origins to Joseph M. Juran – an engineer and management theorist – and the mathematical physicist W Edwards Deming. Their efforts to increase the efficiency of American industry in the mid-1920s laid the groundwork for the development of modern QI.

Now, thanks to the use of QI techniques in other safety critical industries, we know the benefits reach much further – impacting patients, clients, the workforce and the business.

QI aims to address challenges in delivering high-quality care through reviewing and, if needed, changing organisational and professional processes with a view to improving outcomes and efficiency (Table 1).

| Table 1. Examples of QI techniques | |

|---|---|

| Clinical audit | A systematic “cycle” that involves measuring care against specific criteria, taking action to improve it if necessary, and monitoring the process to sustain improvement. As the process continues, further improvements can be made. |

| Significant event audit | A way of formally considering a specific incident in detail to either replicate actions resulting in positive outcomes, or to decrease the likelihood of an incident happening again. |

| Checklists | A common cognitive and communication tool designed to improve the consistency and completeness in carrying out a task by compensating for potential limits of human factors. |

| Benchmarking | A collection of data that enables a point of reference, to help define precise goals and direction, to identify opportunities for improvement, to improve communication between practices, and to elicit change through shared learning. |

| Guidelines | A brief document with specific advice that can help veterinary teams make good decisions through evidence-based information. They differ from protocols: those using the guidelines should take into consideration the specific circumstances of the scenario at hand. |

Do the right thing

EBVM and QI have overall similar goals, but focus on different parts of the challenge.

Paul Glasziou, a physician and professor of evidence-based medicine at Bond University in Australia, describes EBM (EBVM’s counterpart in human health) as focusing more on “doing the right things” through actions informed by the best available evidence from the clinical knowledge base, whereas QI focuses more on “doing things right” and making sure that intended actions are taken thoroughly, efficiently and reliably.

However, the intentions of EBVM and QI are complementary; together, they direct us towards “doing the right things right”.

Two core methods are used in QI to translate “the right things” (evidence) into practical applications: guidelines and checklists.

Guidelines do exactly what they say on the tin – they guide decision-making by incorporating evidence, expertise and patient circumstances into the process.

Checklists drill further down into the process, delineating the stages involved – from diagnosis to treatment – and suggesting at which points to apply particular evidence.

Blue Cross

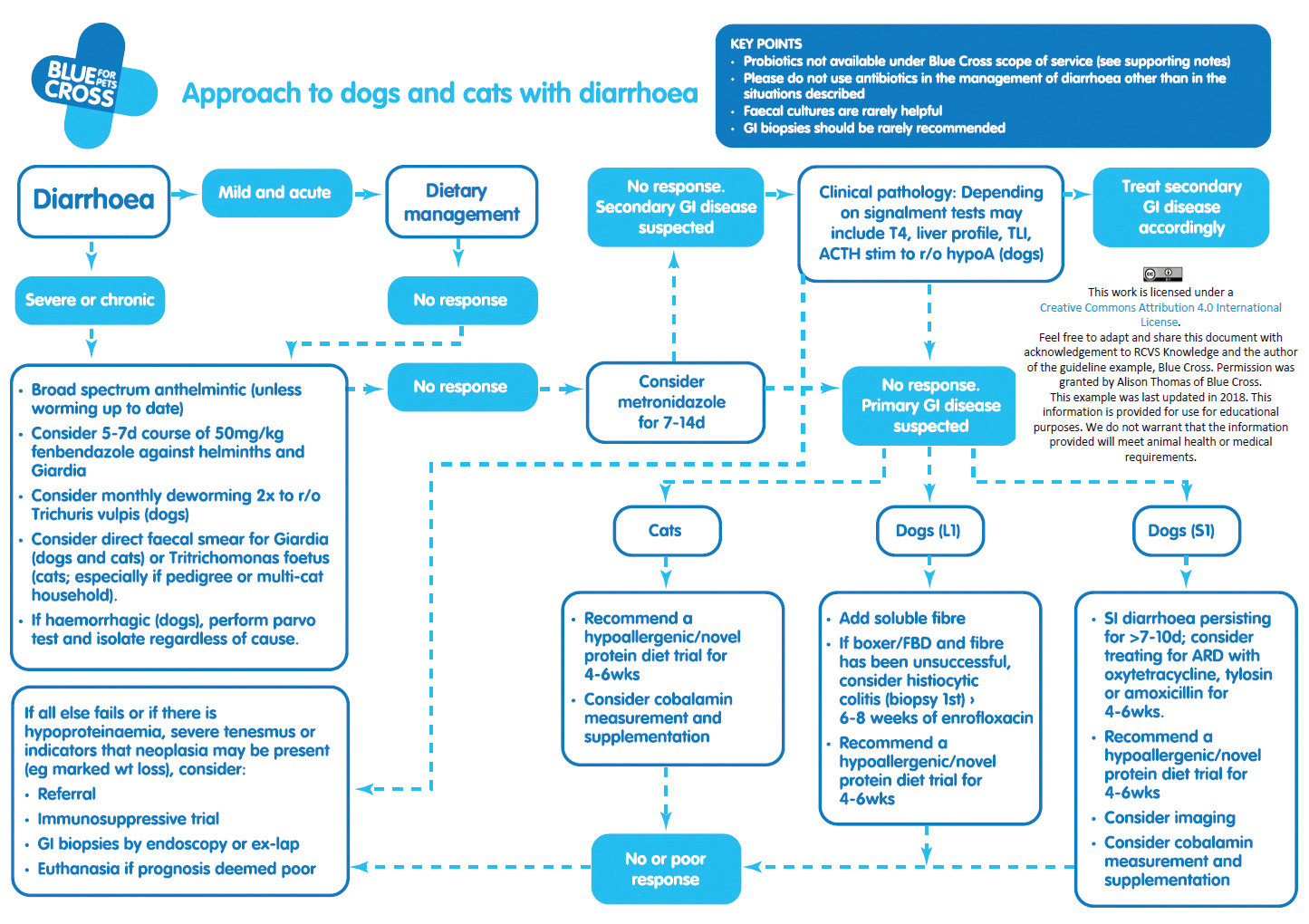

A good example of how to turn evidence – in the form of scientific literature – into tangible guidelines or checklists is Blue Cross’ project to ensure consistency in the treatment of common conditions.

The charity’s head of veterinary services, Alison Thomas, started by identifying the regularly seen clinical conditions that would benefit from a streamlined, evidence-based approach.

More than 60 diseases and syndromes on the resulting list were then allocated to team members, who performed literature reviews to search for the relevant evidence, based on their expertise and personal interest. Once collated, the evidence was discussed by the team, taking into account cost, quality-of-life implications and the charity’s scope of service.

The evidence and information gathered were then developed into guideline documents that allowed room for different treatment options, potential side effects and owner expectations. The result was a set of clear, practical and, perhaps most importantly, malleable guidelines, like the one in Figure 1.

Research as a practitioner

As well as the obvious impact on the clinical aspect of care, developing and embedding QI processes in practice comes with a number of other potential benefits – particularly the experience and skills gained by getting involved in research.

There are numerous ways of engaging with research in practice, to suit all veterinary professionals’ roles, interests and strengths.

Anyone working in a practice can examine processes to ensure the team works efficiently to provide a consistently high-quality level of care to patients and their owners.

This may take the form of reading around a subject to gain a greater understanding of a commonly seen ailment; discussing ideas and experiences with owners through interviews or focus groups; or participating in larger studies by sharing practice data, completing surveys or providing samples.

Delving further into the science does not necessarily mean spending hours in the lab; practitioners curious to understand the pros and cons of certain approaches or treatments relevant to their everyday caseload can find it satisfying and empowering to proactively seek out and even create evidence through structured literature reviews, such as Knowledge Summaries, often enhancing their own skills in the process.

Those with a real appetite for academic research may want to consider a master’s programme in this area – there are options for remote study or to split time between research and practice. Although this represents a considerable time commitment, the opportunity to develop professionally, become part of a new community and acquire transferable skills can be hugely rewarding.

As outlined here, a wide range of research and review activities are available to choose from – all of which have the potential to help improve animal health and welfare.

Further information:

- Attend the RCVS Knowledge stream on Saturday 25 January at SPVS-VMG Congress 2020 (bit.ly/AdaptImproveAchieve)

- Search for the evidence by reading Knowledge Summaries on Veterinary Evidence (www.veterinaryevidence.org)

- Choose from RCVS Knowledge’s suite of QI resources (bit.ly/QIresources) to embed evidence in practice

- Prepare for the next round of VMG Research Awards (https://vetmg.com/vmg-research-awards), opening in spring next year

- Look out for an RCVS Knowledge podcast on research in practice in early 2020 (bit.ly/TheKnowledgeSessions)

Leave a Reply