As I (Shawn) flipped through an issue of Veterinary Times, I came across an article searching for volunteers to help the Olive Ridley Project (ORP) with its research in the Maldives.

It was looking for people to join an expedition for a month collecting data on sea turtles and megafauna in an area that hadn’t been previously surveyed. I knew immediately this was for me; my wife, Laura, and I have always wanted to do some sort of conservation project, but didn’t really know how to go about it.

Having been fortunate enough to have travelled to the Maldives previously, we already knew this was our favourite place in the world. I raced home to show my wife the article. She was interested, but much more cautious than I was, questioning whether we could afford the donation to go. Would our bosses allow us to take a whole month off work? What if, having used our whole holiday allowance for the year, we didn’t enjoy it?

Thankfully, our bosses did grant us permission to go and I managed to persuade my wife to apply. After a short wait, we found out we had been accepted; suddenly, this adventure became very real.

The project

The ORP is a UK-registered charity, founded in 2013 in response to the large number of olive ridley sea turtles found entangled in “ghost nets”. Its mission is to protect sea turtles and their habitats, rehabilitate turtles that have been entangled in nets and use scientific research to increase awareness of the threats faced by sea turtles in the Indian Ocean.

Ghost nets are commercial fishing nets that have been lost, abandoned or discarded at sea. They pose a significant threat to sea turtles – floating on the sea’s currents and sometimes joining up with other nets. They entrap fish, which then act as bait for other marine organisms – such as sharks, rays, dolphins, whales and turtles – that can also become entangled. Olive ridley sea turtles are particularly susceptible to entanglement because they spend most of their time in the

open ocean, unlike the hawksbill and green sea turtles, which spend most of their time on the reef.

Ghost nets can also get caught up on live coral, smother reefs and introduce disease and invasive species to reef ecosystems (Stelfox et al, 2016). Some of these nets can travel hundreds of miles – coming from countries such as India and Sri Lanka, and south-east Asia carried on the currents generated by the Indian Ocean’s south-west and north-east monsoons (Stelfox et al, 2015). These nets don’t degrade much over time as they are made from plastic fibres; therefore, they can go through an almost never-ending cycle of ghost net fishing, lasting many decades (Figure 1).

The ORP physically removes these nets from the sea, gathers important information to understand why the nets end up there, traces their origin, and works with local communities to reduce the problem and repurpose the ghost net materials. This will be discussed further in part two of this article.

The ORP also has a fully equipped, veterinarian-led sea turtle rescue centre situated in Baa Atoll, which rehabilitates injured and sick turtles – forming another vital aspect of its work. In addition to the research expedition volunteer programme, the ORP also runs volunteer programmes at its rescue centre (https://bit.ly/2Y4f1E0).

Research expedition

The specific aim of the research expedition we were to join was to gather data about sea turtle populations in the remote northern Haa Alif Atoll, to help identify and tackle threats to the turtles and their habitat. The ORP runs one of the largest sea turtle photo ID databases in the world, which is crucial for understanding

sea turtle population dynamics. The ORP also collaborates with a local NGO – the Island Development and Environmental Awareness Society – to educate the local community and drive regional marine conservation projects.

Preparation and arrival

Having found out in July 2017 we had a place on the research expedition for February 2018, the latter part of 2017 was spent ensuring we had the equipment needed and planning how to pack for a month away.

Both our excitement and nerves mounted during this time, against a backdrop of friends, family and colleagues all telling us it would be “the experience of a lifetime”.

Before we knew it, we were at Heathrow Airport – suitcases bulging and boarding the Airbus A380 heading east. We had a smooth journey, with flight connections tight in both Dubai and the Maldives capital, Malé. Having drifted in and out of sleep for much of the three flights, it was almost a surprise when we

arrived in brilliant sunshine at Hanimaadhoo International Airport.

We were greeted by the ORP’s project coordinator, Shameel Ibrahim, and marine biologist for the expedition, Nina Rothe, then soon helped on to a speedboat, along with Mark Oldroyd, another veterinary volunteer who had arrived at the same time. In a matter of minutes, we were bouncing across the deep blue waves, heading towards Haa Kelaa, which was to be our home for the next month.

On arrival, we were welcomed by the owner of the guest house we would be staying at, who presented us with frangipani bouquets and fresh coconut to drink. Everyone was so friendly, and our first view of the island told us we had arrived in paradise (Figure 2).

Haa Kelaa is renowned for its two-mile white sandy beach, backed by natural vegetation to the east and gently sloping into the pale turquoise lagoon to the west. It really was stunning, and our pre-travel anxiety rapidly started to dissipate.

Following a delicious lunch of chicken curry, rice and papaya, we were given a small tour around the local area. The mostly single-storey houses lined quiet, wide, clean sand streets. Very few shops or commercial premises existed and people generally got around on foot, or by bicycle, moped or motorbike. It was incredibly

peaceful. Following this, we had time to settle in and unpack, ready for the first full day of work the next day.

Having had a good night’s sleep and a traditional breakfast of flatbread with spiced tuna and coconut, our first proper day started with presentations, covering the aims and work of the ORP and some basic sea turtle biology.

Sea turtles

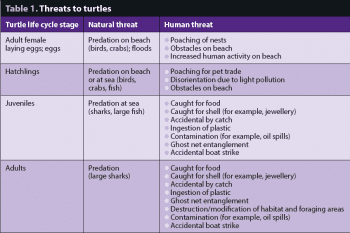

We learned all seven species of sea turtles worldwide are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species (www.iucnredlist.org), and that, naturally, for every 1,000 eggs laid, only 1 turtle will reach sexual maturity and be able to reproduce. Turtles also commonly fall victim to many human activities, which further reduces the survival rate (Table 1).

The sea turtles we would most likely encounter would be hawksbill and green sea turtles. Being an open water species, olive ridley turtles do not actually nest in the Maldives. They are generally only seen in the Maldives when found entangled in ghost nets.

Olive ridley turtles tend to settle on the shores of India in mass nesting events, then make long migrations out to sea. It is, therefore, not uncommon to find more than one entangled in the same net (Stelfox et al, 2015). The olive ridley is the smallest of the sea turtles, measuring up to 70cm fully grown and weighing up to 45kg.

They feed on algae, crustaceans, tunicates, jellyfish, small fish and fish eggs.

Hawksbill turtles feed on sponges on the coral reef – protecting the corals from sponge overgrowth. They also eat jellyfish and are important for keeping jellyfish populations under control. Unfortunately, plastic bags and packaging floating in the sea can easily be mistaken for jellyfish by the turtles. It is possible for turtles to ingest so much plastic they cannot feed normally and then starve to death.

Healthy hawksbills grow 75cm to 90cm in length as adults and can weigh up to 70kg. They are critically endangered (the final category prior to being extinct in the wild), with the worldwide population being fewer than 10,000 (IUCN Red List, 2017).

Green sea turtles, by comparison, are herbivores – grazing on sea grass meadows and eating algae. They can grow up to 120cm in length and weigh up to 160kg. Green sea turtles are less common in the Maldives than hawksbill turtles and are categorised as endangered (IUCN Red List, 2017).

The hawksbill turtle and green sea turtle can be distinguished from each other by their body size and beak shape, and the appearance of their shells (Figure 3).

Surveys and photo ID

The authors also learned each sea turtle has a unique scale pattern on its face – a bit like a human fingerprint (Figure 4). This can be used to identify individual turtles – enabling accurate assessment and recording of turtle numbers on a reef. The sea turtle photo ID and database is another important aspect of the ORP’s work.

We spent four days each week carrying out reef surveys, which involved travelling to three different locations each day by boat, snorkelling for one hour along the reef at each location in a transect line, while recording turtle and other megafauna sightings, and trying to obtain turtle ID photographs.

For accurate identification of each turtle spotted, left and right facial photos and one carapace photo are required. These pictures are then compared with those in the database to assess whether the turtle has been previously seen and entered into the database, or a newly identified animal – in which case, it would be added to the database.

For each turtle, the time and location of the sighting, species, approximate body size, sex (if adult size), activity and photograph numbers had to be recorded on to a waterproof slate during the survey. This information was later entered into the relevant database.

However, we soon learned this whole process was easier said than done. Turtles, although large, are exquisitely well-camouflaged and can be almost invisible among the coral – even when they’re right underneath you. Most turtles are also quite shy and can swim away while you are trying to take photographs.

Additionally, some of the reefs we would visit were quite deep (10m to 15m), and some had strong currents or large swells. Overall, this often meant only the most proficient duck (free) diver would succeed in getting usable pictures.

The amount of information to gather – along with staying in the transect line, while notifying the other team members of each sighting and trying to obtain pictures – meant the input for each sighting was quite intense and could be a stressful few minutes. A lot had to be done in a very short space of time. We also found out some sites appeared to have quite large turtle populations, and this could result in multiple turtles being sighted at the same time. This had the potential to cause confusion unless the team was extremely quick, slick and well-organised.

Megafauna

Megafauna sightings were recorded for the duration of the time we were at sea – as opposed to solely during the one-hour snorkel surveys. Megafauna includes dolphins, rays and sharks, and we were exceptionally fortunate to see a wide range of species (Figure 5).

The most magical encounter for us was with the Mobula (previously manta) rays. These have the largest relative brain of all fish and as long as you stay quiet and still in the water, they are happy to swim around you and even appear curious (Figure 6). We were also very lucky to have numerous dolphin sightings, including seeing spinner dolphins jumping out of the water spinning, and having a few pods join us to ride the boat’s bow waves.

Data entry

At the end of each boat day, we would gather all of the photographs for each individual turtle, select the best left and right lateral facial and carapace shots, and check these against the pictures in the database (Figure 7).

If the turtle was a re-sighting, this would be noted on the data spreadsheet. If it was a new turtle, then, provided we had all three photographs, it would provisionally be added to the database. Confirmation would be given, after review, by Jillian Hudgins, the project scientist who is in charge of the national Maldivian sea turtle photo-ID database.

The information obtained for each turtle was also entered into the ORP’s database and the Turtlewatch Maldives database. Turtlewatch Maldives is a partnership programme between the Marine Research Centre and IUCN – aiming to collect standardised data on foraging and nesting sea turtles throughout the Maldives.

Data (time, site, species, number of animals and behaviour) was also entered into a separate spreadsheet for other megafauna. Data entry involves a huge amount of work and we were very slow at first, so it was common to be finishing late into the night.

Life at sea

That said, boat days were incredible; it was so peaceful to commute to and from work this way, and provided several hours of time to watch the ocean – and observe dolphins, flying fish and birds – while contemplating life, the universe and everything.

Our boat was a traditional Maldivian dhoni. The captain and his crew were supremely skilled at navigating the reefs – even in quite rough seas or at night. They went out of their way to ensure our safety, including, at one point, putting their boat between us and a large fishing vessel that had strayed out of the boating lane and over the reef we were surveying.

We all fell in love with our time at sea, but we also found land-based work rewarding and interesting, which will be discussed further in part two.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anderson Moores Veterinary Specialists and The Barn Animal Hospital for allowing time off to take this amazing journey; the Olive Ridley Project for accepting us as volunteers and for kindly allowing the reproduction of images for this article; and Shameel Ibrahim, Nina Rothe and Mark Oldroyd for being fantastic companions during this experience.

Leave a Reply