Flea and tick control form an essential part of routine parasite control for pet cats and dogs. Fleas are highly prevalent on domestic cats and dogs, with 28.1% of cats and 14.4% of dogs found to be infested in the UK (Abdullah et al, 2019).

Tick-borne disease also represents an ongoing and growing risk to UK dogs and their owners, through increasing numbers and activity of endemic ticks, and the introduction of exotic species.

It is important flea and tick control advice is accurate and based on recent data to minimise disease transmission risk and reduce the risk of household infestation. Innovation in the veterinary and pharmaceutical industries is also important to provide effective parasiticides and tools to aid compliance.

Latest flea and tick data

The fundamental difference between pet infestations with fleas and ticks endemic in the UK is flea populations establish in homes, whereas ticks are mostly

encountered outdoors.

Fleas are present throughout the UK, with the vast majority on cats and dogs being cat fleas – although poultry fleas, hedgehog fleas and dog fleas have also been found (Abdullah et al, 2019).

Cat fleas are well-suited to living in the humidity and temperatures maintained in most UK homes, with 95% of a typical flea infestation existing in

the home as eggs, larvae and pupae.

The most common species of ticks found on UK dogs continue to be Ixodes, the vectors of Lyme disease (Abdullah et al, 2016; Wright et al, 2018). Although real-time data from the Tick Surveillance Scheme (TSS) and Small Animal Veterinary Surveillance Network still indicate peaks of Ixodes tick activity in the spring and summer, increased activity also appears to exist throughout the summer, with the potential to take place at any time of year (Wright et al, 2018).

Pockets of the tick Dermacentor reticulatus have been long-established in the UK in west Wales, Devon, Essex and London. D reticulatus is the vector for Babesia canis, a cause of potentially life-threatening anaemia in dogs, and while B canis had been absent from the UK, these ticks presented an opportunity for B canis to become endemic if introduced through travelling dogs returning from abroad, or pet imports that may be infected or carrying infected ticks.

Since the establishment of Public Health England’s (PHE) TSS in 2005 the highest number of submitted D reticulatus ticks from dogs that had not travelled outside the UK was in 2016 (Medlock et al, 2017). This combination of factors has led to an endemic foci of B canis infection establishing in Harlow, Essex, with B canis being confirmed in local Dermacentor ticks and in untravelled dogs (Phipps et al, 2016; Woodmansey, 2016). Further untravelled cases were confirmed in Romford, east London in 2016 and Ware, Hertfordshire in 2017 (Woodmansey, 2017).

Rhipicephalus sanguineus are being seen regularly on imported and travelled dogs. The Big Tick Project, examining dogs across the UK for ticks, found of all the dogs that had travelled in the two weeks prior to their inclusion in the study, 30.2% were infested with R sanguineus (Abdullah et al, 2016). Although it is unlikely R sanguineus would establish outdoor endemic populations in the UK, it can complete its life cycle in three months, which has allowed it to infest UK homes in a similar way to fleas. This is a concern, as these ticks may carry zoonotic pathogens such as Rickettsia conorii.

Records of R sanguineus received by the TSS are increasing each year, and in the past two years two house infestations have been confirmed (Hansford et al, 2017).

Latest thinking on significance of infestations

Fleas are a cause of allergic dermatitis and vectors for a variety of infections, including Bartonella henselae (cause of cat scratch disease), Rickettsia felis (cause of spotted fever), haemoplasmas (cause of feline infectious anaemia) and Dipylidium caninum tapeworms.

A total of 11.3% of flea infestations on UK cats and dogs have been found to be positive for Bartonella species (Abdullah et al, 2019). People are thought to be exposed to this pathogen primarily through flea faeces, making flea control vitally important for preventing zoonotic exposure to this pathogen.

Ticks are also very competent vectors of disease-causing pathogens. A total of 2.37% of Ixodes ticks on dogs have been shown to carry Borrelia species, which cause Lyme disease (Abdullah et al, 2016).

The recent cases of B canis in untravelled dogs from Harlow, Romford and Ware demonstrate the potential for this potentially life-threatening pathogen of dogs to establish in the UK. The potential for spread has also been demonstrated by B canis being confirmed in a tick from one of the endemic foci in Wales (de Marco et al, 2017).

R sanguineus on travelled pets is capable of transmitting numerous pathogens, including Ehrlichia canis and zoonotic Rickettsia species. The European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites UK and Ireland has also seen an increased number of E canis cases reported in travelled dogs in 2017 and 2018.

Control measures, and the use of latest data and innovations

All cats and dogs may be exposed to fleas, leading to the establishment of household infestation. Even indoor cats may be exposed if adult emergence from pupae are triggered by pets or owners outside, leading to newly emerged adults entering households.

The use of a routine effective flea adulticide is, therefore, crucial on all cats and dogs all-year round.

The presence of poultry fleas on some household pets means the possibility of environmental infestation from bird nests in attics, gutters and other household locations should be considered. Infestation can also occur from adjoining poultry houses.

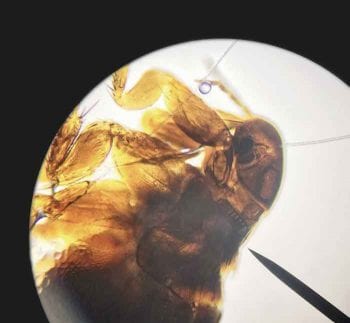

Cat and dog fleas have both pronotal and genal combs (Figure 1), while bird fleas only have pronotal combs (Figure 2). Examination of fleas under the microscope will allow these combs to be examined if bird flea infestations are suspected.

A risk to cats and dogs of year-round tick exposure also exists, with increased risk from the early spring through to late autumn (Abdullah et al, 2016; Wright et al, 2018).

Some pets will be at considerably higher risk of exposure based on lifestyle; therefore, a risk assessment should be made to establish if tick prevention is required in an individual pet. Several factors should be considered.

- Are dogs walked on pasture that is shared by ruminants or deer? Deer and ruminants are reproductive reservoirs for Ixodes species ticks, especially Ixodes ricinus, with individual animals potentially carrying very large numbers of ticks.

- Do dogs walk on land containing tall grass or bracken? These provide questing sites for ticks.

- Do cats and dogs visit known geographic areas of high tick density? Certain areas of the UK have been demonstrated to have high tick densities, including the New Forest, Yorkshire Dales, Lake District and Scottish Highlands. The Big Tick Project – looking at the prevalence of ticks on pet dogs – confirmed these patterns, although discrepancies such as the apparent absence of ticks from parts of the Scottish Highlands could be explained by the lack of participating veterinary practices in these areas. The Big Tick Project website allows the number of ticks found in a local geographic area to be checked by postcode. The recording and publicising of ticks found in practice is also useful via websites and social media to help pet owners and veterinary practices assess local geographic risk. The TSS also records geographic data from where ticks are submitted (Wright et al, 2018).

- Do cats roam freely or hunt? Such activity is more likely to lead them into undergrowth, burrows or nests containing ticks.

- Do dogs live in – or visit – Essex or adjoining counties? Those that do should be considered at higher risk of Babesia canis exposure.

- Do cats and dogs have a history of tick exposure? A history of tick infestation implies a lifestyle that will put them at risk of further exposure in the future.

- Has the pet been imported or travelled abroad? These pets should be treated and checked for ticks to reduce the risk of exotic tick introduction and foreign pathogen exposure. If, after risk assessment, it is decided preventive tick treatment should be employed, this should consist of a preventive product and checking for ticks at least every 24 hours.

- Preventive tick treatments. Use of a drug that rapidly kills, such as the isoxazolines, or repels and kills, such as pyrethroids, will greatly reduce tick-borne pathogen transmission. Only licensed treatments with safety and efficacy profiles in the target species should be used.

- Checking for ticks at least every 24 hours. This is essential in high-risk pets and those that have travelled abroad, as no tick preventive product is 100%

eff

Figure 3. Ixodes species nymph. ective, and challenge in some geographical foci can be very high. Latest TSS data has suggested the majority of ticks are located and found around the head, face, legs and ventrum (Wright et al, 2018). Nymphs are extremely small and easily missed, so tick removal alone should not be relied on for high-risk cats and dogs (Figure 3). Ticks should be removed with a tick removal device or fine-pointed tweezers. If tweezers are used, the tick should be removed with a smooth upward pulling action. If a tick hook is used, a simple “twist and pull” action is employed. After ticks have been removed, they should be submitted to the TSS for identification. This is useful for national surveillance, but also to indicate what pathogens individual pets or people may have been exposed to. Apps have been developed in some mainland European countries for photographs of ticks to be uploaded for subsequent identification. While this technology has not yet been developed commercially in the UK, it is still useful to take images of ticks on mobile phones for identification if owners are unable or unwilling to submit ticks themselves.

Product choice is key to effective flea and tick control. Innovations over the past decade in flea and tick products means effective spot-on preparations, tablets

and collars are available.

Endectocides, including endoparasite activity, mean that, where appropriate, products can be minimised and still come in a variety of formulations, increasing

compliance and the ease with which flea and tick prevention products can also be incorporated into overall parasite control programmes.

It is essential products are applied correctly and on time, and recent advances in technology are aiding this. Automated text message and reminder systems prompt clients to remember when to apply treatments, while social media, apps and practice websites can be used as platforms to educate clients on flea and tick control, as well as how to apply products.

Short educational videos, blogs and podcasts are becoming increasingly easy to produce on mobile phones and uploaded on to websites or social media pages. In

using this technology, a personal touch can be added to parasite control advice and the client-practice bond increased.

Conclusion

The whole practice has an essential role to play in the formulation and implementation of flea and tick control plans. It is vital, therefore, the latest epidemiological data and technological innovations are used to give best advice to clients, and compliance.

By making data readily available to the practice team by website links, journals and referenced news publications, such as Veterinary Times, everyone giving advice can be confident they are using peer-reviewed and current information.

By also getting a variety of people involved in vet practice social media, recording blogs and engaging with clients through a variety of media, bonds between practices and clients can be strengthened and compliance increased. This will increase both animal and human health as a result.

Leave a Reply