Eye cases can pose a difficult clinical conundrum in first opinion practice.

They are often made even more tricky due to limited equipment and inadequate lighting conditions. Battling with the settings on a dusty ophthalmoscope with a dying battery to look at a patient attempting to burrow face first into the chest of a worried owner in a brightly lit consult room springs to mind.

Here are a few simple things that can make your examination more fruitful:

- A dark room. Switch off the lights and close the blinds. This will reduce glare to allow a clearer view of the ocular surface and dilate the pupils to give you a bigger window to look through when examining the fundus.

- Adequate restraint. Keep the patient’s head steady and in a position where you can access the eye to enable a more in-depth examination. Proper restraint of the patient by the owner or a nurse, with local anaesthetic applied to an uncomfortable eye, will help you enormously.

- Charged-up equipment. A bright light source – even if you are managing with a pen torch or otoscope – will make all the difference to your examination.

- Clean equipment. Cleaning away years of dust and fingerprints will drastically improve your view. Inexpensive lens cleaning wipes or sprays are safe to use on the viewing aperture of your ophthalmoscope and indirect lens (also an otoscope, lab microscope and even smartphone camera lens) and can be bought inexpensively.

The equipment you will need to perform a basic work-up is as follows:

- A focal light source. An ophthalmoscope will give you the added bonus of magnification and the ability to change the brightness, but a transilluminator, pen torch or even otoscope are sufficient enough to illuminate the eye.

- An indirect lens. Indirect ophthalmoscopy is a difficult skill to master, but learning the correct technique and getting plenty of practice will help you to reap the rewards when examining the fundus of the eye. An acrylic condensing lens can be bought for around £40.

- A Schirmer tear test and fluorescein stain.

- A camera with flash. A camera with a flash is a very useful tool for scrutinising the initial presentation of a case, monitoring progress and even gaining specialist advice.

Equipment such as tonometry and a slit lamp will allow you to get more from your ocular exam, but they are not always available in first opinion practice.

How to use an ophthalmoscope

The ophthalmoscope is a versatile and essential piece of equipment, but its full potential is rarely used beyond that of an expensive pen torch. Many brands of ophthalmoscope exist, all with their own quirks and differences, but all are variations on a theme. Taking the time to familiarise yourself with the dials and settings will help you significantly when it comes to your exam.

The ophthalmoscope light is a rheostat, like a dimmer switch, which means you can control the brightness. The temptation is often to turn it to the maximum brightness for the whole of the exam, but it can be useful to dim the intensity when performing distant, direct ophthalmoscopy.

A whole array of light beam shapes is available, but the only two you need are the biggest circular beam and, occasionally, the slit beam setting. The colour filters of most use are the white light and the cobalt blue light for assessing fluorescein uptake.

The number indicates the ophthalmoscope’s refractive power setting, in dioptres, and can be altered by turning the dial on the side.

What do the refractive power values mean? Changing the refractive power of the ophthalmoscope changes the focal point:

- The zero setting means no refractive power.

- Positive values (black/green). These increase dioptic power to bring the focal point closer to you.

- Negative values (in red). These diverge the beams of light and push the focal point away from you.

The best baseline setting on the ophthalmoscope for you is determined by your own eyes. If you do not require glasses, or are wearing contact lenses, this will be zero.

If you wear glasses, remove them and set the number to your prescription. For short-sighted eyes the setting will be in the negative (red) values; for long-sighted eyes it will be in the positive (black or green) values.

Distant direct ophthalmoscopy

Distant direct ophthalmoscopy assesses the clarity of the visual axis and the symmetry of the pupils (Figure 1).

How do I perform this technique?

To perform distant direct ophthalmoscopy:

- In the dark.

- Have the patient at arm’s length.

- Put a hand on the patient’s chin or nose to help steady its head and keep it looking at you.

- Stand directly in front of the patient so you can examine both eyes in the same field of view.

- The brightness setting should be of moderate light intensity.

- Look through the ophthalmoscope rather than hold it at the side of your head – this aligns the beam of light with your own eye.

What should the number be on my ophthalmoscope?

The number on your ophthalmoscope should be your baseline setting.

What should I be able to see?

You should be able to see the tapetal reflection in both eyes.

Tips for finding the reflection:

- The tapetum is located dorsally. Look from below the patient’s eyeline. Attract the patient’s attention by calling its name or making a squeaking, hissing or whistling noise.

- Examine the brightness of the reflection and the size of the pupils. Look for the presence of any opacities and the size of the pupil.

What does this help diagnose?

Distant direct ophthalmoscopy helps diagnose opacities in the visual axis, such as cataracts or anisocoria – asymmetrical pupils (Figures 2 and 3).

Close direct ophthalmoscopy

Ophthalmologists tend to use close direct ophthalmoscopy for in-detail examination of the fundus – preferring to use a slit lamp to examine the anterior structures in the eye. However, direct ophthalmoscopy can be used very effectively for the examination of the whole eye.

What should the number be on my ophthalmoscope?

Start with your baseline setting on your ophthalmoscope to examine the fundus.

- Increasing the positive dioptric power (green or black numbers) brings the focal point of the ophthalmoscope towards you. This makes it possible to view structures inside the eye that are closer to you than the fundus – such as the vitreous, lens, iris or cornea – in magnified detail while allowing you to remain at the same distance from the patient.

- Before you look through the ophthalmoscope, familiarise yourself with the direction you need to turn the dial on the side to increase the positive refractive power

-

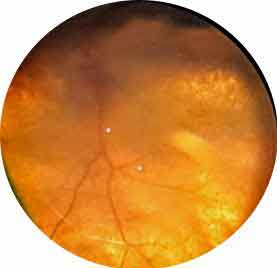

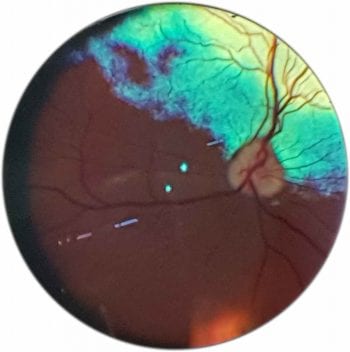

Figure 7. A view with direct ophthalmoscopy. A detailed, magnified view of the fundus. Be aware the brightness of the light decreases with increasing dioptric power (the same as the change in brightness on a light microscope from ×10 to ×40), so increase the brightness if you are struggling to visualise structures at higher settings.

The settings required for a magnified view of the ocular structures vary according to your own eyes, but as a rule of thumb: fundus 0, lens +10, iris +15, cornea +20, and eyelids +25 to +30.

How do I perform this technique?

To perform close direct ophthalmoscopy:

- Do so in the dark.

- Start by performing distant direct ophthalmoscopy as described previously.

- Maintain your view of the tapetal reflection in one eye as you move in from arm’s length until you are close enough to rest a finger from the hand holding the ophthalmoscope on the patient’s head.

- Visualise a structure on the fundus, such as a blood vessel or a spot of pigment or the optic nerve head. Once visualised, keep it in view and adjust your distance with small movements towards or away from the patient until it comes into focus. Once in focus, stay at this distance away from the patient and rotate yourself to look around the fundus.

- If you want to look at something closer to you, such as the iris or cornea, stay at the same distance away from the patient and adjust the dial on the side of the ophthalmoscope to increase the positive dioptres until that structure comes into focus (Figure 4).

When fundus NAD in your notes translates to fundus not actually detected

The fundus is one of the most exquisitely beautiful structures in the body, but such significant variation exists between individuals, breeds and species that it is very difficult to detect abnormalities. The examination techniques require practice and perseverance to gain any useful diagnostic information.

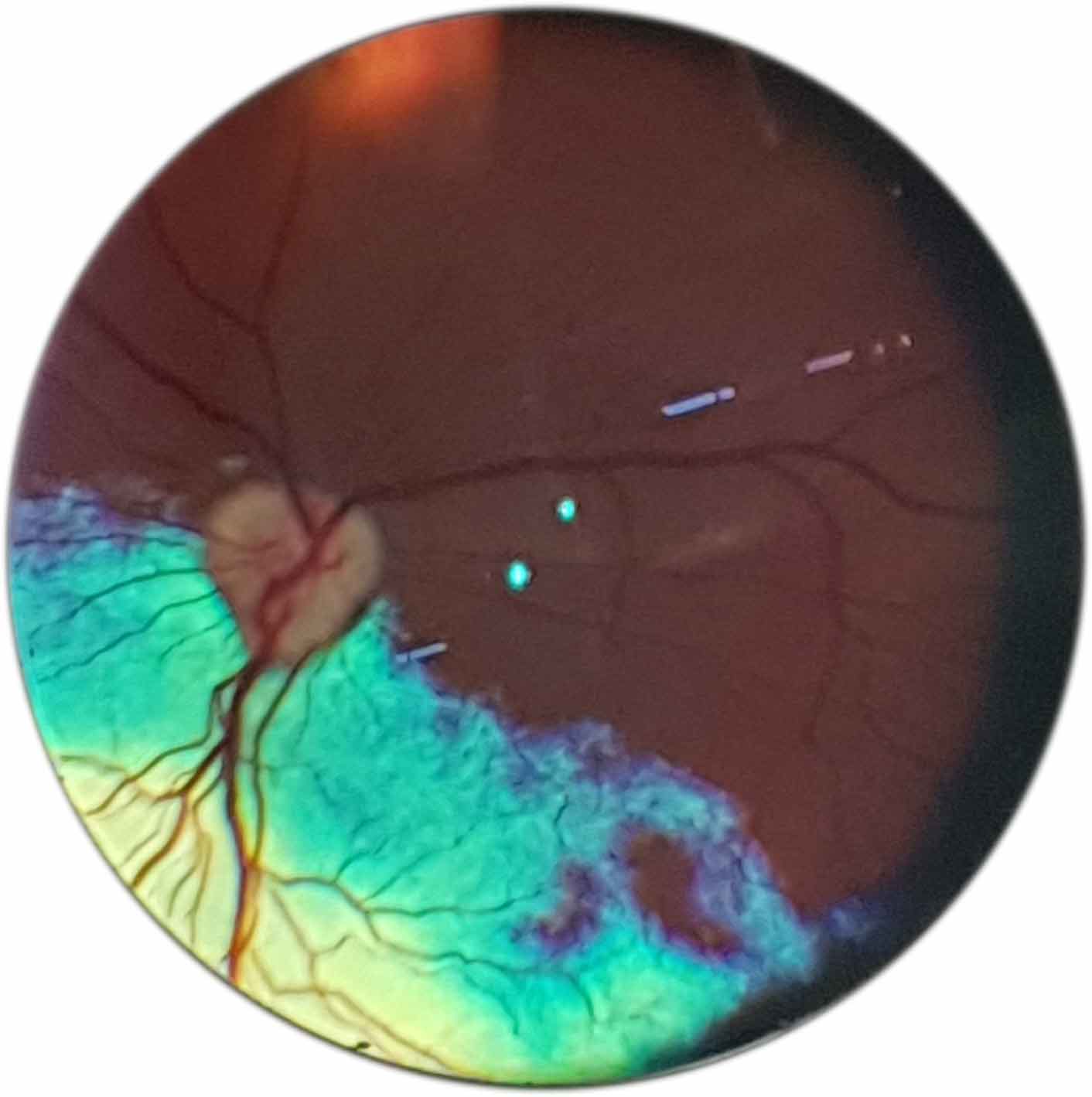

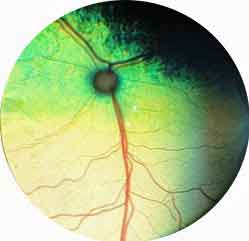

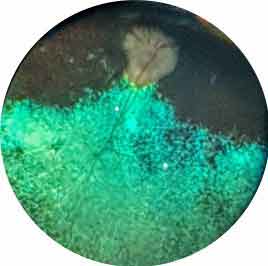

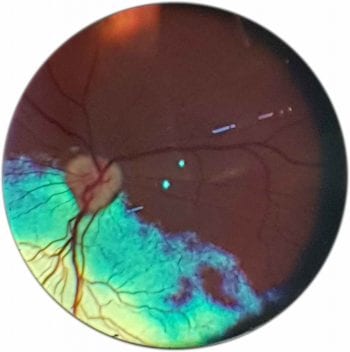

The fundus can be examined using both direct and indirect ophthalmoscopy. Indirect ophthalmoscopy provides an overview of the fundus, but direct ophthalmoscopy enables a more detailed examination of a smaller area. (Figures 5 to 7).

Indirect ophthalmoscopy

Indirect ophthalmoscopy is one of the most difficult techniques to master, but can be endlessly rewarding as it affords an overview of the fundus, which you can then apply direct ophthalmoscopy to examine areas of interest in fine detail.

Equipment

1. Condensing lens

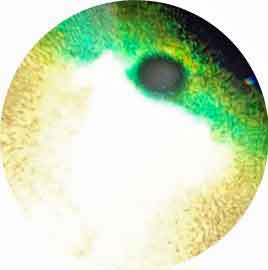

The lens creates an upside down, back to front virtual image of the fundus. The standard condensing lens is a 20D lens, although some prefer the 2.2 (22D) pan retinal lens, while others favour 28D or 30D lenses for small animal patients.

Glass lenses produce a sharp image of extremely high quality. They are more expensive – costing around £300 – heavy and easily chipped, and must be handled with a lot of care.

Acrylic lenses are the cheap and cheerful option, costing approximately £40. They are lightweight and resilient enough to withstand being dropped on the floor. They are a great starter lens, as they are versatile and can produce an image of diagnostic quality.

The technique is just as tricky with either glass or acrylic lens – requiring the same amount of practice and perseverance.

Which way round should the lens be?

If you look at the lens from above, one side is flat and the other is more curved – that is, it has a “belly”. The flatter side should be positioned facing the patient and the belly of the lens towards the examiner – that is belly to belly (Figure 8). Some lenses have a metallic rim to indicate the side that should face the patient (Figure 9), but others are less helpful, and it can be useful to put a dot of paint to quickly identify this side.

2. The light source

A focal light source at moderate to low light intensity such as a transilluminator, pen torch, direct ophthalmoscope or otoscope. The condensing lens does what it says on the tin – it condenses the beam of light as it passes through. The beam emitted from your light source will be intensified, so it is important to use the lowest possible brightness to make it tolerable for your patient.

How do I perform this technique?

To perform indirect ophthalmoscopy:

- Ask the person restraining the patient to raise the head slightly by supporting the chin (Figure 10).

- Hold your light source close to your eye. The beam of light needs to be in the same plane as your visual axis as if the light was emitted from your own eye.

- Find the tapetal reflection in one eye. You will not be able to see an image with your lens without the tapetal reflection (Figure 11).

- Hold your condensing lens between your thumb and index finger, and rest your middle and ring fingers on the patient’s temple (Figure 12).

- While maintaining your view of the tapetal reflection, rotate your hand holding the condensing lens to place the lens in front of the eye. Imagine slotting the lens perpendicular to the beam of light passing from your eye to the patient’s fundus (and therefore parallel to the eye).

Upside down and inside out

When you move the lens to look around the periphery of the fundus, remember the image is inverted, so when you move the lens medially, the image will move laterally and when you move dorsally, the image will move ventrally and vice versa (Figure 13). This can be very confusing to begin with, but with enough practice, will become second nature.

Tips for success

Within the fundus the tapetum sits dorsally and the optic nerve head sits slightly ventrally. Place the patient on a table and crouch down so you are looking up towards its eye. This positioning will help to initially identify the tapetal reflection, and when you place the lens in front of the eye and stand up slightly, it will aid your view of the ventral fundus and the optic nerve head.

Dilate the pupil with a drop of 1% tropicamide. This will give you a wider aperture to look through and minimise the need to move the lens to look around the periphery of the fundus.

Binocular head sets are often used by ophthalmologists instead of monocular light sources, such as a pen torch. This has the advantage of allowing placement of both hands on the patient to help with positioning of the head.

The light source is positioned between the examiner’s eyes. The head set has a series of mirrors to provide a coaxial light beam in line with each eye, which improves depth perception and can aid the diagnosis of papilloedema, retinal detachment, tumours or other mass lesions, and cupping.

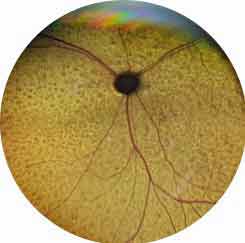

So much variation exists in the normal fundus, can anything help me work out what is actually abnormal?

Variations in fundus colour and pigmentation are usually the least clinically significant, but the most distracting findings as they draw the attention of the examiner away from the areas that can actually lead you to a diagnosis (Figure 14).

Generally, the most clinically significant areas are:

- Diameter and pattern of the blood vessels. Why?

- Thin, attenuated – chronic retinal degeneration, for example, progressive retinal atrophy (PRA).

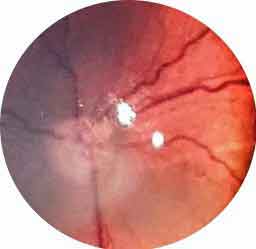

- Blurry, red – retinal haemorrhage; white – perivascular cuffing, hyperlipidaemia.

- Tortuous, wiggly – vascular disease, for example, hypertension.

- Colour and size of the optic nerve head. Why?

- Large and puffy – papilloedema; if blind – optic neuritis.

- Small and pale – chronic retinal disease, for example, PRA or glaucoma.

- Consistency and brightness of the tapetal and non-tapetal fundus. Why?

- Tapetal hyperreflectivity is a sign of retinal thinning or absence – for example, retinal degeneration.

- Tapetal hyporeflectivity is a sign of cells, fluid, pigment or retinal folds obscuring the tapetum – for example, retinal oedema or infiltrates, retinal detachment, retinal dysplasia, retinal pigment epithelial dystrophy.

- Tips for success

Always examine both eyes – most normal variations in fundus appearance are roughly symmetrical.

Remember, if you identify an abnormality on indirect ophthalmoscopy, use direct ophthalmoscopy to examine this area in magnified detail.

Taking ocular images with a smartphone

Photographing the eye is an excellent way to document the initial presentation and progression of a case, but they can also be sent to ophthalmologists for a specialist opinion. For example, Langford Vets runs a free email advice service (eye-advice@langfordvets.co.uk) and can provide more detailed information for cases with a good quality photograph attached.

- Tips for success

1. Clean away significant ocular discharge and fluorescein stain using saline flush.

2. Turn your flash on.

3. Make sure the camera is focused on the area of interest.

4. Take the picture in a dark room.

5. Attract the patient’s attention, so it is looking directly at you.

Acknowledgement

This article was reviewed by Claudia Hartley BVSc, CertVOphthal, DipECVO, FRCVS and RCVS specialist in ophthalmology.