Arthritis is a very common problem in older people and older dogs, but until recently was considered an uncommon problem in cats.

However, we now recognise that it is a significant cause of pain for many elderly cats, but it shows itself rather differently in cats compared to dogs and so can easily be missed unless a feline-specific approach to diagnosis is adopted.

How common is arthritis in cats?

While no doubt exists that arthritis is a very common problem in older cats, it is difficult to put an accurate figure on its prevalence. This difficulty arises not least because of the lack of any widely accepted and practically applicable diagnostic test for the condition, so published studies have used different approaches to identify affected cats, as well as focusing on different target populations.

Most studies have looked at the prevalence of radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease in cats, either retrospectively or prospectively. These studies highlight how common the problem is, identifying radiographic changes in:

- 34% of cats of all ages (Clarke et al, 2005)

- 61% of cats of six years of age and older (Slingerland et al, 2011)

- 90% of cats more than 12 years old (Hardie et al, 2002)

Those studies that include a range of ages consistently identify a strong correlation between increasing age and increasing prevalence of arthritis (Clarke et al, 2005; Slingerland et al, 2011; Lascelles et al, 2010), but also identify a significant level of degenerative disease in at least one joint in younger cats.

Joints most commonly affected are hips, stifles, tarsus and elbows (Lascelles et al, 2010). Spondylosis of the thoracic and lumbar spine is also very common.

We must also recognise that relying on identifying radiographic changes alone to diagnose arthritis will inevitably lead to an under-estimate of the prevalence of degenerative joint disease (DJD) because radiographic changes only become evident once bone remodelling or cartilage mineralisation has developed.

A significant proportion of damaged and painful joints have not yet developed these changes: a postmortem study of 30 adult cats indicated that 71% of the stifle joints examined had cartilage damage, but were radiographically normal, and this was also the case in 57% of coxofemoral joints, 57% of elbows and 46% of tarsal joints (Freire et al, 2011).

Given that identifying radiographic changes is not a reliable means of identifying all affected cats, another approach is to assess the prevalence of clinical signs attributable to joint pain: large surveys of vets and owners in the UK and globally suggest that around 30% of cats of all ages were exhibiting signs of arthritis (Zoetis anti-nerve growth factor veterinarian quantitative market research, 2018).

Is feline arthritis a painful condition?

In humans, arthritis is painful and it is recognised that this is also so in dogs. It is reasonable to assume that this is the case in cats, too, but on a superficial assessment this may be less evident. Cats are inherently stoical creatures; they are fundamentally self-sufficient hunters and as such they have to be able to function well despite a level of pain, weakness or disease. This tendency to “hide” signs of pain can contribute to it being overlooked by owners and by veterinary professionals, and this problem of under-recognition of pain is amplified because even when cats do show signs of pain, they exhibit it differently to dogs and humans.

Cats with arthritis rarely present with a limp, but they do exhibit clear gait and behavioural changes as they adapt their activity and mobility to accommodate the chronic pain. Affected cats are also found to be more bad-tempered than pain-free cats (Lascelles et al, 2012), a tendency that is also recognised in people suffering from chronic pain.

How does arthritis present in cats?

While arthritis can cause lameness, in cats this is usually only evident in severe cases, or where there has been acute injury to a joint already affected by arthritis. Much more commonly cats with arthritis will show changes in behaviour as they adapt their lifestyle to cope with their chronic pain.

Affected cats are more reluctant to extend themselves by running, jumping, climbing, or going up or downstairs. They will tend to use their forelimbs to help pull themselves up on to a chair or on to their owner’s lap and will take stairs one at a time, or “bunny hop” up or down rather than moving fluidly from one stair to the next.

The elbows are often affected, so hesitancy in jumping down or difficulty in going downstairs is as significant as difficulty in jumping up or in climbing stairs. Most affected cats spend more time resting, less time grooming, and may become “grumpy” and withdrawn.

How should we diagnose OA in cats?

In veterinary practice we generally reach our diagnoses through a combination of the clinical history provided by the owner; changes identified on physical examination; results of appropriate further investigations, which are aimed at either confirming a diagnosis or ruling out other differential diagnoses; and finally the response to appropriate treatment of the diagnosed condition.

In the case of feline OA this approach needs to be adapted to place much more weight on the owner’s observations of gait, behaviour and mobility changes, and a positive response to treatment, supported to a lesser extent by findings from an appropriate feline-orientated physical examination and with much less emphasis on “proving” the diagnosis using further diagnostic testing – that is, joint radiography.

Identifying characteristic behavioural and gait changes, and achieving a positive response to analgesia, have been shown to be a reliable means of identifying arthritis in cats (Lascelles et al, 2007; Klinck et al, 2012), whereas physical findings are often very subtle and easily overlooked.

Mild to moderately affected joints may not have easily detectable joint effusion and usually maintain a good range of joint movement. The cat may show few if any overt signs of joint pain: it may become tense or “wriggly” when its joints are handled as the only sign of discomfort. Cats with OA can also be challenging to examine because the presence of chronic pain is associated with low tolerance of handling (Lascelles et al, 2012). Take care to avoid firm restraint and over-manipulation of the joints – while the cat may not show clear signs of discomfort during the examination it may be in significantly more pain afterwards.

Radiographic changes are also frequently subtle or absent – especially in early disease – and general anaesthesia is required to get well-positioned diagnostic quality radiographs. Unless the cat is undergoing anaesthesia for some other reason the cost, stress and risk of anaesthesia are rarely justified given the lack of correlation between joint pain and presence or severity of radiographic changes.

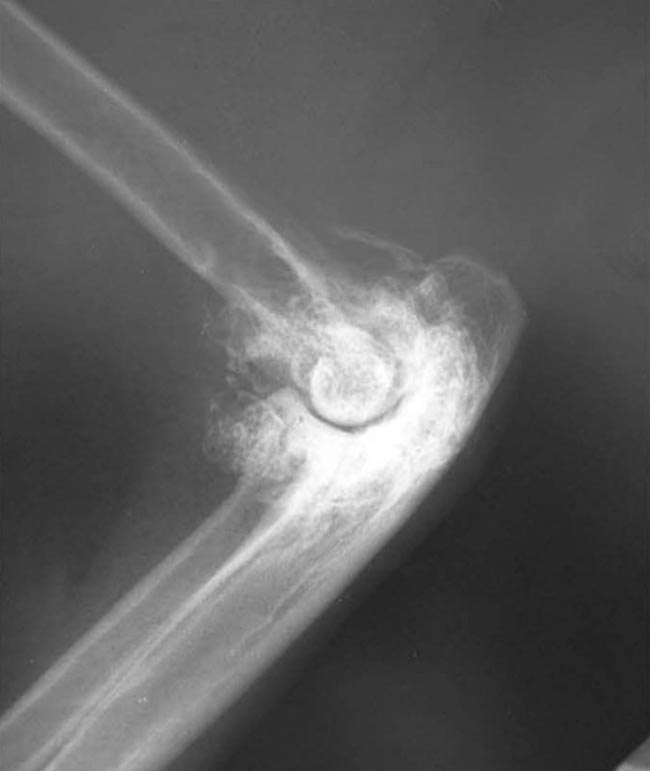

Painful joints may be radiographically normal, and joints exhibiting extensive bony remodelling (Figure 1) may appear quite comfortable on physical examination. In a study of 13 cats whose owners recognised that they had impaired mobility, 33% of joints had evidence of both pain on manipulation and radiographic change while 67% of joints had radiographic evidence of DJD, but no apparent pain on manipulation (Lascelles et al, 2007).

Asking the right questions

If we are to rely heavily on the owner’s observations and reporting of behavioural and gait changes in their cats to diagnose arthritis, it is important that we ask the right questions and educate owners as to the significance of the changes they are seeing.

The behavioural and gait changes associated with arthritis are very often recognised by owners of older cats, but are interpreted as indicators of old age rather than as signs of pain. In many cases the owner will not perceive them as significant enough to be mentioned at visits to the veterinary practice despite being well aware that changes have occurred.

Even when owners are aware that the signs they are seeing relate to arthritis they tend to assume that this is both inevitable and untreatable, and so do not bring their cat into the practice to discuss this issue. It is therefore essential to raise owner awareness of the problem, and the available treatment options, by appropriate history taking and discussion during routine health checks or when the cat is presented for other problems.

A mobility questionnaire sent to the owners of older cats along with their booster vaccination reminder, or given to them to fill in while in the waiting room, can help to highlight problem areas and focus the mind.

The recent development of a simple checklist of gait and behaviour changes that have been shown to be reliable indicators of arthritis (Enomoto et al, 2020) and that are readily identifiable by owners should provide a clinically expedient screening tool to improve our ability to identify affected cats and to help us to increase owners’ awareness of the problem.

In the study a large number of questions were posed and responses were assessed for sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy. The six questions that performed best have been included in the checklist, which aims to be quick and simple for owners to complete (Figure 2).

If an owner answers “yes” to any question further, more detailed assessment is required, which should include further discussion of recent behavioural and gait changes, and where possible assessing video clips of the cat moving around its own home, as well as physical examination, response to treatment and possibly joint radiography in selected cases.

Conclusion

Arthritis is a very common problem in cats, which often goes unrecognised and even when it is recognised it often goes untreated. A number of factors contribute to the under-diagnosis of this chronic painful condition, and a clinically expedient approach to diagnosis relying more heavily on owner-observed changes in mobility and behaviour could have a major impact in uncovering the magnitude of the problem.

The problem of under-treatment of feline arthritis is discussed in a second article in this series, identifying some common barriers to treatment and outlining the many treatment modalities that are now available to effectively manage this common cause of chronic pain.

Call-outs

OA is a common problem in cats, estimated to affect more than 60% of cats aged six years and older (Slingerland et al, 2011).

Poor correlation exists between radiographic evidence of arthritis and the presence of cartilage damage (Lascelles et al, 2010), and poor correlation between radiographic changes and identifiable joint pain (Lascelles et al, 2007).

Cats with arthritis can be identified by changes in gait, such as going up and downstairs one step at a time, or with a “bunny-hopping” action, rather than in a smooth fluid movement from one stair to the next.

Leave a Reply