Fat deposition is a normal physiological response to a positive energy balance. However, obesity is defined as adiposity to an extent that it has a negative effect on health, leading to reduced life expectancy and/or increased health problems.

It is increasingly obvious that obesity is common and has significant detrimental effects on the health of horses and ponies, similar to the human and companion animal populations. While 26% of pet cats and 25% of pet dogs are overweight, UK studies report that between 21% and 45% of horses and ponies are fat or very fat1,with rates in some populations of native ponies being as high as 70%2.

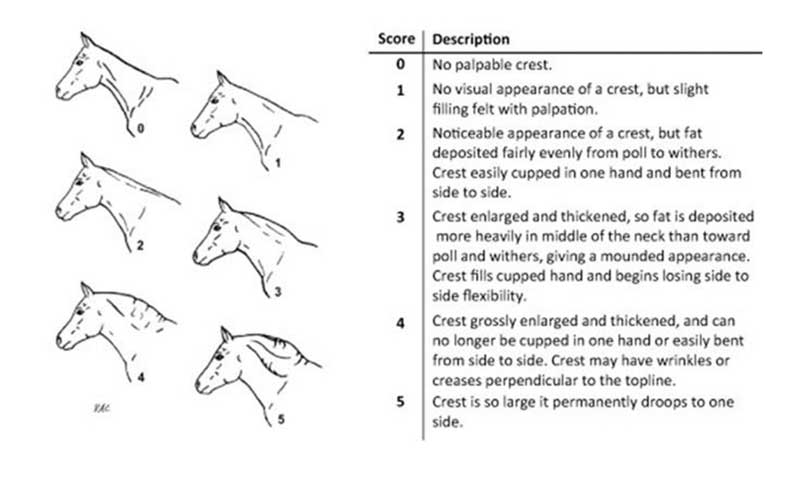

Worldwide, obesity has been reported in 10% of mature Icelandic horses in Denmark3, 8% to 29% of horses in Canada4, 24.5% of Australian pleasure horses and ponies5, and 51% of mature light-breed horses in the US6. Obesity may be generalised or regional (Figures 1 to 3); regional adiposity, based on a cresty neck score of greater than 3 out of 5, was present in 33% of horses in south-west England7.

Draught-type, cob-type, British native and Welsh breeds8, Shetland ponies5, Rocky Mountain horses, Tennessee walking horses, quarter horses, Warmbloods, and mixed-breed horses were all more likely to be obese compared to Thoroughbreds6.

Obesity is also more common in animals described as good doers, animals used for pleasure or non-ridden, and show or dressage animals8. In addition, owners consistently underestimate the level of obesity of their animal5 and the perception of ideal weight for show animals is greater than for other disciplines9.

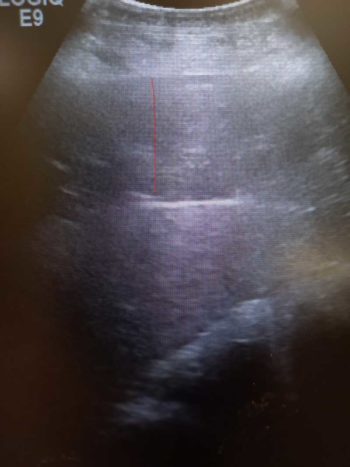

It should also be remembered that obesity may be external (namely, visible or palpable subcutaneous fat deposits), but can also be internal (Figure 4) with the accumulation of adipose tissue within and around organs and muscle. On average, an obese animal will have equal amounts of external and internal fat accumulated, and so only 50% of the adipose tissue accumulated will be visible.

Why are horses becoming obese?

The reasons domesticated animals develop obesity are similar to those attributed to obesity in humans – namely physical inactivity combined with the consumption of excessive calories. As a herbivorous species, horses have evolved to rely on grass forage alone for their nutritional requirements. Therefore, during the summer and autumn, horses should ingest increasing quantities of available forage and gain adiposity in preparation for the winter when food tends to be scarce.

Increased secretion of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) by the pituitary pars intermedia during these seasons stimulates appetite and adipogenesis. These changes represent a critical survival mechanism that ensures stored energy in the form of body fat is available throughout the winter months. Normally, the period of food scarcity is finite and the acquired fat stores are depleted just prior to the onset of spring and resumption of grass growth. Therefore, in the wild, acquisition of adipose tissue in summer and autumn is essential for winter survival.

The development of insulin dysregulation (ID) is a critical component of this winter survival mechanism, which seems to develop and resolve in parallel with the acquisition and depletion of additional fat stores at the start and finish of winter, respectively. Therefore, horses and ponies have evolved to be “yo-yo” dieters, getting fat in the summer or early autumn, and thin again over winter.

The modern husbandry practices of providing excessive calories in the form of high-quality pasture and bucket feeds, physical inactivity, stabling, and the use of rugs to help maintain body temperature year-round all promote fat storage and/or decrease the use of stored fat, and consequently the acquisition of excessive adiposity and its chronic persistence. This is further compounded by owners striving for their horses to look their “best” year-round.

The perception of “best” has morphed over time, from horses that are well muscled for work or sport to horses that are instead well covered in fat. Many owners do not appreciate the difference between muscling and fat deposition, and the trend toward promoting increased fat deposition has been re-enforced by rewarding obesity in the show and dressage arenas, and by the frequent depiction of obese horses as role models on websites, in the equestrian press and elsewhere.

Additionally, obesity is often trivialised with obese animals depicted in cartoons, the use of endearing terms such as “cuddly”, “tubby” or “podgy”, and the lack of a social stigma associated with keeping an obese animal. By contrast, the site of a thin or emaciated horse evokes horror and accusations of cruelty. The result is the persistence of obesity, and hence, ID year-round.

Adverse health effects of obesity

Obesity has been shown to have several adverse systemic effects, including the following:

- Insulin dysregulation. Adipose tissue is the largest endocrine organ in the body, producing a range of hormones (adipokines) with normal physiological roles. In obesity, adipose tissue dysregulation results in overproduction of some adipokines and underproduction of others. Some of these adipokines antagonise or sensitise to insulin, with the alterations in production resulting in overall antagonism of insulin and hence insulin dysregulation.

- Inflammation. Evidence shows obesity is associated with systemic10, adipose tissue11 and uterine inflammation12.

- Oxidative stress. Evidence suggests obesity is associated with systemic oxidative stress, as well as localised oxidative stress within the pancreatic islets13 and lamellar tissue.

- Stimulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Evidence shows obesity-associated stimulation of the HPA axis with increased free cortisol concentrations due to decreased binding proteins and altered tissue cortisol metabolism. Cortisol antagonises insulin and so this may contribute to ID.

-

Figure 3. Horse with fat accumulation around the withers and loin. Vascular and endothelial dysfunction. Feeding a haylage diet to induce obesity to Standardbreds was associated with a linear increase in mean arterial blood pressure during the weight gain period14.

- Altered faecal microbiome. Studies have demonstrated that host-phenotype has major effects on equine faecal microbial population structure; changes were predominantly associated with the obese state, confirming an obesity-associated impact in the absence of nutritional differences15.

- Altered cell-mediated immunity. While metabolic status did not influence humoral responses to an inactivated influenza vaccine in horses, those with equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) had a reduced cell-mediated immunity response to vaccination compared to metabolically normal, non-EMS control horses16.

As a result of these effects, many health disorders are associated with obesity in the horse, including:

- endocrinopathic laminitis

- increased risk of hyperlipaemia

- impaired thermoregulation

- decreased fertility

- osteochondrosis dissecans in foals born to obese mares

- behavioural disorders

- increased blood pressure

- orthopaedic disease through increased loading

- preputial and mammary oedema and dermatitis

- ventral oedema, possibly as a consequence of compromised lymphatic drainage

- colic resulting from pedunculated mesenteric lipomas

- inappropriate lactation, possibly via effects on thermoregulation and prolactin production

- reduced growth rates in foals of obese mares, caused by excessive mammary adiposity and reduced milk production, and/or exaggerated compensatory growth rates once weaned

- respiratory compromise and equine asthma

- pharyngeal collapse

- poor performance

Assessment of obesity

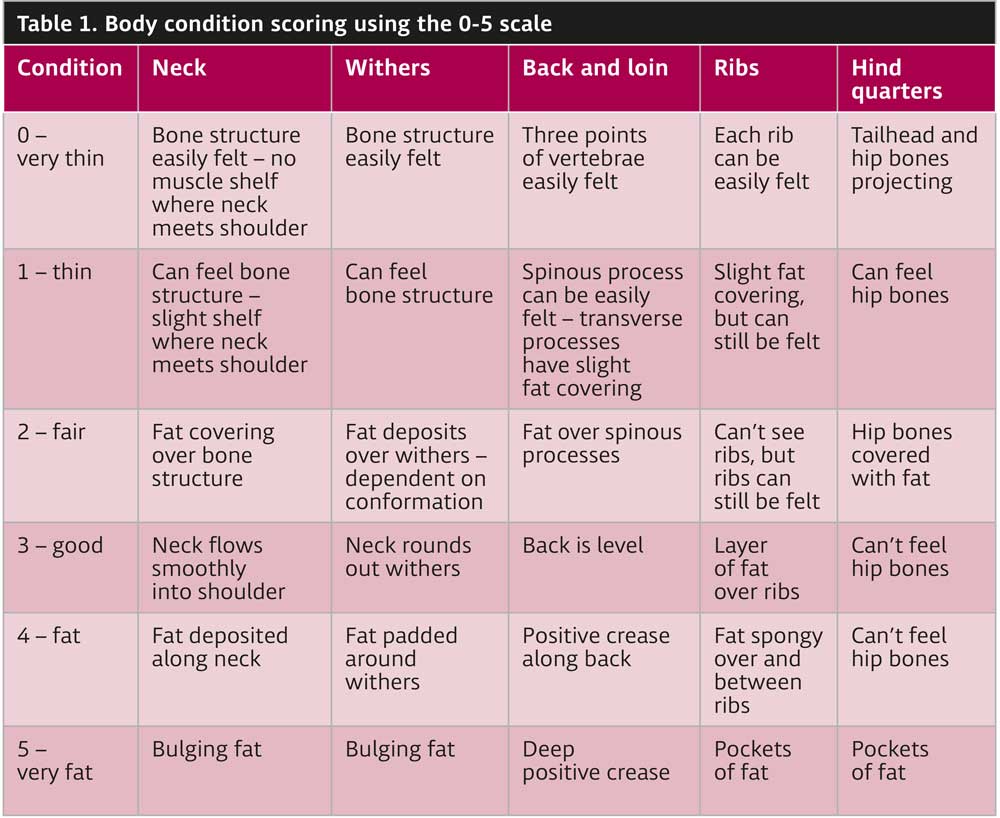

In the research setting, obesity is most accurately assessed at postmortem by carcase dissection or by administration of deuterium oxide17. However, in clinical practice, generalised obesity is assessed by body condition scoring (BCS)18, which can be performed using a 0-5 (Table 1) or 0-9 scale19. The latter is more robust, but seems to be used more frequently in the research setting.

Either scale is acceptable provided the denominator is stated. Horses with a BCS of 7 out of 9 or greater are considered to be obese18, as fat is likely to account for greater than 20% of bodyweight (BWT). In very obese horses, fat mass may even exceed 40% of BWT. Using a five-point scale, a BCS more than 3 out of 5 is considered as obese. Regional adiposity is assessed using cresty neck scoring (CNS; Figure 5).

Ultrasonographic measurements of fat depth at specific anatomic locations can be used to assess adiposity, but have their limitations20,21. The assessment of retroperitoneal fat depth by ultrasonographic examination of the ventral midline may be useful in demonstrating horses that are thin on the outside, but fat on the inside (so-called TOFIs; Figure 4).

Serum insulin and the adipose tissue derived hormone adiponectin are independent risk factors for laminitis2, so measurement of both in overweight animals can be useful in persuading owners their horse has metabolic disease and would benefit from a weight loss programme. However, neither can be used as a marker of obesity itself or to identify when adiposity becomes damaging to health.

Management of obesity

Importance of communication

Knowledge of what is currently fed and what changes are possible under the individual circumstances will facilitate formulation of a bespoke weight loss programme. Success hinges on understanding the behaviour and attitude of the owner to ensure they can be supported most appropriately to implement effective and lasting change.

Gathering data and ensuring that clients engage takes time, so it is often more appropriate to arrange a specific appointment dedicated to formulating a plan tailored to the needs of the individual animal and getting the client to complete a questionnaire ahead of this consultation expedites the process.

During the consultation, care should be taken to not judge the owner (for example, embarrassing them for overfeeding an obese equid or making an owner feel like they have made an obvious mistake), or use obesity-shaming terminology (for instance, fat or chunky).

Judgement and guilt are barriers to communication, limit information gathered and prevent effective care, while connection built through effective communication likely will foster compliance. You should serve as a guide to the conversation rather than act as an authoritarian, centring the owner in the dialogue instead of talking at the owner.

You should provide and discuss options, identify obstacles for the owner and provide solutions – being cognisant about wording and non-verbal communication. Once the consultation is complete, you should give clear recommendations, avoiding ambiguity, to ensure the owner understands why the recommendations/suggestions matter, and what the rationale and follow-up are. The agreed plan should be written down and given to the owner to ensure it is recalled correctly.

Weight loss plan

Most weight loss plans follow a similar format of implementation – a regime of dietary changes in conjunction with increased exercise in sound animals. In some horses, discontinuation of overfeeding and provision of more appropriate feed sources may be sufficient to induce weight loss. Veterinary involvement frequently follows diagnosis of EMS, which, in turn, often occurs after laminitis has developed.

In these patients, weight loss programmes will need to be more aggressive as risk of future laminitis is higher, additional desire exists to improve ID and exercise cannot be included as part of the management programme. If weight loss programmes are being implemented prior to the development of laminitis, or other obesity related morbidities, more time and less necessity exist to remove horses from pasture and control every aspect of the diet.

An ideal target for weight loss is 0.5% to 1% of body mass (BM) weekly; more rapid weight loss is associated with more rapid subsequent weight gain. The targets should be written down alongside the weight loss plan provided to the owner and it is important targets are reviewed regularly, and management adjusted accordingly.

Dietary recommendations

Overweight or obese animals should be fed a diet based on grass hay (or hay substitute), with low (lower than 10%) non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) content and cereals avoided. Maximising the calories coming from forage is important to help promote satiety, and support gastrointestinal health and normal foraging behaviour. Additionally, the insoluble fibre in forages is slowly fermented by gut microbes, supports a neutral hindgut pH and the symbiotic gut microbiota, and promotes overall gut health.

A daily allowance of 1.25% to 1.5% of actual BM as dry matter intake, or 1.4% to 1.7% of actual BM as fed, is widely recommended. Soaking hay for six hours in cold water or one hour in warm (16°C) water before feeding will leach water-soluble carbohydrates. However, this does not reliably decrease the NSC content to lower than 10% in every case11 and, ideally, forage should be analysed after soaking. It should be remembered that steaming hay does not reduce NSC content.

Feeding haylage should generally be avoided, as haylage typically has a higher NSC content, is more palatable, so intakes may be higher, and seems to result in a greater insulin response than a comparable hay22. However, some haylage can have a low NSC content and if fed in restricted quantities may be suitable if it has been analysed. Barley straw can be fed to maintain appropriate levels of fibre and total intake, while reducing calorie intake; a recent study demonstrated that horses fed a 50:50 hay:straw diet lost weight, while those fed hay did not23.

The forage should be divided into three to four feeds per day and strategies employed to prolong feed intake time, such as use of haynets with small holes, double hayneting, haybags and haynets hung from the ceiling in the middle of the stable.

In most overweight animals, any access to pasture is going to severely frustrate attempts at weight loss. It is, therefore, best to remove the horse from pasture, at least initially. However, access to non-grassed turnout should be encouraged. When an animal is to be turned out to pasture, while this will have the beneficial effect of increased exercise and allow social interaction, methods to restrict intake should be used, such as strip grazing, track systems, restriction of turnout time, grass muzzles and keeping pasture height short through topping.

Forage-only diets do not provide adequate protein, minerals or vitamins and so a low-calorie commercial ration balancer product that contains sources of high-quality protein, and a mixture of vitamins and minerals to balance the low vitamin E, copper, zinc, selenium and other minerals typically found in mature grass hays is recommended.

Advice on feeding needs to be simple and specific for owners to be able to implement the changes in their daily life. For most owners, compliance will be improved if a specific “recipe” is provided, which dictates exactly what quantity of exactly what feed (namely, the trade name) is required.

Providing general advice and telling owners they need to feed 1.5% BM of a feed with less than 10% sugar is unlikely to result in good compliance, because it may be hard for them to put these figures into practice. Instead, vets should be dispensing weight tapes and luggage scales for weighing forage alongside a written feed plan.

Owners should be reminded the use of a single scoop for different feeds can result in overfeeding, as they measure volume rather than weight, with the weights of feeds varying considerably, and the scoop needs to be calibrated for each feed. The diet plan can then be written in terms of the owner’s specific scoop.

Finally, owners should be encouraged to weigh out the total amount of food for the day, before being subsequently split into separate portions. Creating and weighing individual portions has been seen to lead to a tendency to feed at the top end or even slightly over the recommended weight each time, and weighing once reduces the percentage error.

Exercise

Unless a musculoskeletal reason exists for not doing so, animals should be exercised daily, as this has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and decrease food intake, as well as consume calories. Intensity and duration of the exercise undertaken needs to be gradually increased in any animal according to fitness level. However, it should be remembered exercise is not a substitute for dietary restriction.

Recommendations around desired exercise levels are largely opinion-based, yet to achieve compliance any exercise programme needs to be both specific and realistic. In a consensus statement24, the following exercise recommendations were made:

- Horses without laminitis: heart rate 150 to 170 beats/minute (fast trot to canter unridden) for at least 30 minutes, 5 or more times/week. However, this can’t be achieved from day one, as it will depend on the initial fitness of the patient.

- Horses with previous history of laminitis: low-intensity exercise on a soft area (heart rate 130 to 150; canter to fast canter, ridden or unridden), 30 minutes, 3 days per week, always monitoring for signs of lameness.

Alternatively, a protocol for 50 minutes of exercise was proposed recently with a 10-minute warm-up at walk, and then alternating trot sets and walk breaks of 5 minutes each, finishing with a 5-minute cool down25. It was suggested this protocol be performed 5 days per week. As horses become fitter, the trots sets can be replaced with canter.

Rugging

Horses can thermoregulate at temperatures between 5°C and 25°C – and, therefore, require no additional measures to control their body temperature, such as rugs between these temperatures. Horses that are acclimatised to lower temperatures can thermoregulate at temperatures as low as -10°C to -15°C. Above 10°C, horses prefer not to be rugged except in extreme wet/windy weather conditions.

Therefore, if the weather is neither wet nor windy then rugs are only required below 5°C and acclimatised horses may only require rugs below temperatures as low as -10°C.

Unnecessary rugging represents a welfare concern in causing horses to become too hot in warmer weather, such that they are unable to thermoregulate, whereas depriving horses of rugs is less likely to impact on their welfare.

Provision of a field shelter that provides protection from the wind and rain is a far better solution to cold weather than rugging. However, geriatric horses may be less able to thermoregulate at lower temperatures.

Pharmacologic agents

Pharmacologic agents should be considered for short-term use (three to six months) in animals that are weight-loss resistant, cannot be exercised for lameness reasons or are at a high risk of laminitis and require more rapid weight loss than can be achieved with management changes alone.

Levothyroxine is the most appropriate pharmacologic treatment for promoting weight loss through speeding up the metabolic rate, and has also been demonstrated to improve insulin sensitivity26. It is essential for compliance with the dietary recommendations when using levothyroxine, or weight loss is unlikely to result due to the side effect of polyphagia.

No licensed product is available in the UK; however, levothyroxine can be prescribed under the cascade at a dose of 0.1mg/kg by mouth once a day for a period of three to six months, or until the target for weight loss is achieved. When treatment is to be discontinued, it is recommended the dose is halved for two weeks, then halved again for a further two weeks before treatment is stopped.

Monitoring weight loss

Weight loss in response to dietary restriction and increased exercise should be monitored every four to six weeks by the owner. Ideally, this should be done using a weighbridge. However, this is not usually possible. Instead, the most reliable method involves heart and belly girth measurement (using a measuring tape), or use of a weight tape, as these will decrease as bodyweight decreases. However, it should be remembered these tapes will not consider focal adiposity.

Body condition score will often remain unchanged for a prolonged period, as it is a non-linear scale and marked weight loss will be required before the score will change, resulting in the owner becoming disheartened when no improvement is apparent.

Cresty neck score is also less reliable, as the crest contains a large amount of fibrous tissue that will remain even with marked loss of adipose tissue. Therefore, neither are useful for monitoring weight loss. Instead, it is important to find markers that provide owners with gratification, and heart and belly girth are, therefore, the most suitable. It is also important to consider regular veterinary check-ins to ensure the weight loss is going according to plan, and allow any necessary adjustments to be made.

Targets are helpful and provide a sense of purpose, so it is useful to provide charts to monitor morphometric characteristics and bodyweight. Targets for exercise based on working towards the owner’s aspirations (for example, to get the horse fit enough to enter a sponsored ride or undertake a specific activity) are also a powerful motivator1. Use of apps that allow exercise targets to be set and progress to be tracked can also be helpful.

If the target rate of weight loss is not achieved after four to six weeks, compliance should be questioned, and the horse’s diet and management reviewed. If no issues of compliance are seen, the amount fed should be reduced by 0.25% of bodyweight. However, it is preferable not to decrease forage provision to below 1% of target bodyweight, as this may increase the risk for hindgut dysfunction, stereotypical behaviours, ingestion of bedding or coprophagy.

Once the target weight is achieved, it is important that monitoring of weight by the owner is continued, or experience from other species indicates diet and management changes will not be maintained in a large proportion of cases – and many will return to an obese state.

Equids that have lost weight may still exhibit ID and, if they do, they should continue to be fed low sugar/starch (below 10% to 12% NSC) feeds that will limit the glycaemic – and, therefore, insulinaemic, response. A high-fibre, low-cereal diet will be healthier, so any return to feeding cereals after weight has been lost should be discouraged. Any subsequent gain in weight, however transient, may be associated with decreased insulin sensitivity – and, therefore, increased laminitis risk.

Leave a Reply