I was born in 1940 and dragged up in industrial Lancashire – Lowry country – betwixt Bolton and Manchester. At age 11, I went to the local grammar, which was just average – but then, I was a below-average pupil, so it did well by me.

I passed six of eight O levels (GCSEs) sat, scraped three A levels and secured entry to one of three schools of pharmacy applied to – Chelsea, now part of King’s College, London. After three hard years, I secured a 2i (2:1). I decided, within three months of joining the Chelsea BPharm course, that neither retail, nor hospital, pharmacy were for me, for the positive reason that the taught science just blew my mind. I set my sights, there and then, on being the first British pharmacologist to be awarded the Nobel Prize. In this, I did not succeed, but I was, in due course, to receive even greater accolades from my veterinary colleagues.

Therefore, I never did the one-year pharmacy apprenticeship, but went straight into a PhD programme with the head of pharmacology at Chelsea College. It proved to be a travelling scholarship, which ended up at the RVC.

State of the nation, 1960s

Similarities exist between the state of the nation in the 1960s and the 2010s, but, inevitably, differences exist, too. Likewise, in society at large. At societal level, the so-called swinging sixties did swing for some, due, in no small part, to “the Fab Four”, and the 60s also nurtured the hippie generation.

“We had never had it so good” – we knew that to be the case, because Prime Minister Harold Macmillan told us so. Thus, the 1950s post-war austerity was superseded by new-found affluence for some and yet, despite the new found freedoms (love, speech and lunches), there was student unrest in UK universities.

Unrest was more prominent in France, however, where leftish students on the Left Bank threatened insurrection. In France, in due course, things quietened down, as the student insurrectionists had second thoughts and opted for lucrative careers in international banking.

At the RVC, on the other hand, all was sweetness and light – well almost. Teachers taught and students studied for their chosen career, with never a thought of establishing a Trotsky paradise in the UK. Nevertheless, Andrew Higgins (RVC undergraduate 1968 to 1973, later my PhD student, co-author and long-standing friend) reminds me there were more than ripples on the University of London and RVC fronts.

In 1968 to 1969, The London School of Economics was revolting, London students were campaigning for the overthrow of Douglas Logan as principal, and this did have an effect on the RVC. A working party was constituted to evaluate pre-clinical teaching. This was, in its time, quite revolutionary or at least was thought to be so by many enraged staff. Controversially collected were comments on staff and courses, and a report was duly issued, the contents of which will not be revealed here.

State of the RVC, 1960s

In terms of buildings and staff numbers, the college was a small fraction of its current size. Most activity centred on Camden, and the Hawkshead campus was known simply as the Field Station.

One degree – the BVetMed – existed, but a small minority of students could, and did, opt to do the intercalated BSc in physiology. The academic staff had “tenure”, which meant a job for life, regardless of performance, with the result staff worked either very hard or barely at all.

The management structure was strongly hierarchical and paternalistic. For example, we had a senior dining room, for entry into which males were required to wear a tie or cravat. And we had a “Governors’ Cloakroom”, reserved, yes, for the ablutions of governors and no others. This does not imply criticism from me. History is a different country, and we should not judge the values of the time by present norms, while accepting, of course, the splendid standards of political correctness we all benefit from in the 21st century.

Arrival at the RVC

As already mentioned, as a PhD student I moved with my supervisor. We started at Chelsea (three months) in October 1961 and then moved to the medical school, University of Birmingham, in January 1962. We left Birmingham – a city, incidentally, I rarely saw in daylight, such was the commitment to my research studies. The next stop was London (again), but with no college in sight. I was occupationally challenged.

All I could do for the next five months was read the literature in Senate House library, then – just in time for a great Christmas present – the good news came: “we are going to the Royal Veterinary College, old thing”, courtesy of Emmanuel Cipriano Amoroso.

I took up residence at the Camden campus as a PhD student in January 1963. Our office and laboratory were one and the same, in the basement of the canine block – a room we inherited from the famous heart surgeon Donald Longmore, in which he conducted experimental heart transplants on dogs. He was a lovely chap.

While I had my small Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) maintenance grant, my supervisor was at the RVC on a grace-and-favour basis – no salary. For her, the good news came when she informed me “we are going to Perth, old thing”. On close questioning of the actual location, it was revealed to be not the one in Scotland, but the one in Western Australia. To be honest, I had by then had a bellyful, and I refused to travel any further. This was November 1963.

So, she went and I stayed, and then I was more formally placed in the Department of Physiology and Chemistry – headed by the late, great Prof Amoroso. What a man, but more of that later. Suffice it to say, this internationally recognised reproductive physiologist/anatomist, the world authority on placentation, was now supervising my PhD studies on drugs and hormones acting on the kidney – wonderful news, while it lasted.

When Amo went off on a sabbatical to America for several months, I was left in the capable hands of the reader in physiology, Frederick Roland Bell. All this did not matter much, because I knew what I had to do in the lab: the problem was not lack of supervision, but lack of time. The DSIR grant was limited to three years. A happy solution was to follow.

Through others’ mistakes I learned, on my PhD programme, to design, conduct, analyse and also to replicate experiments. Replication is less fashionable these days, but the recognition of its importance to acceptance of data and theories is thankfully growing. On checking my thesis, I see I conducted one study on the actions and interactions of isoprenaline and dichloroisoprenaline in the rat on four occasions – similar results every time.

A permanent, tenured position

The three-year DSIR maintenance/support grant came to a natural end on 30 September 1964. By this time, Amo was back from the US and well aware of my demise; most of the practical work was done, but some months of writing lay ahead, with no visible means of financial support.

It was late August/early September when Amo said, one day, “come to see me tomorrow morning, boy”. I had no idea what was in store. I fetched up and he took me down to the office of the then principal Ron Glover.

We sat down. Amo said nothing, but Ron started the questioning: “Are you enjoying your time at RVC; what are you hoping to do job-wise in the future; have you had time to look at the pharmacology course here at RVC; how do you think you could improve the undergraduate course?” Oh my life, the penny dropped: I was being interviewed for a job.

I was near to tears (of joy), but managed to spout on my best bull faeces and landed the job, starting 1 October 1964. I was occupationally challenged no more, appointed assistant lecturer in pharmacology in this venerable institution, the oldest veterinary school in the English-speaking world, and with a royal appellation to boot (incidentally, it will be known to Veterinary Times readers the RVC now is the number one veterinary school in the known universe). I forget the shillings and pence, but the first month’s salary was £69 for an annual total of £828 gross.

A new supervisor, Prof Amoroso

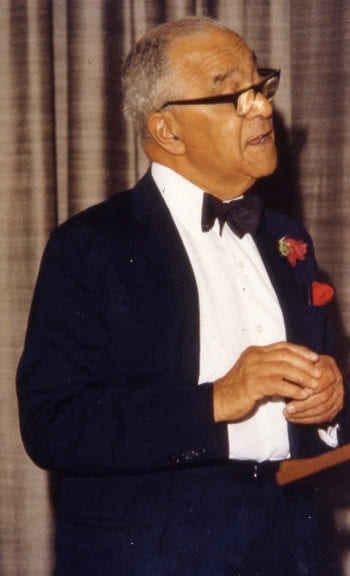

For me, Amo was a giant of a man – physically and intellectually. I was told (but never verified) that he was fluent in five languages, and additionally had a passing knowledge of Arabic. He was a fellow of the Royal Society and an honorary associate of the RCVS, awarded, I believe, rather quickly after his Royal Society fellowship.

He was a writer of wonderful prose and he was my PhD supervisor. In physical stature, he reminded me of a description given of a Mr Hudson, a Victorian railway king: “His frame is naturally broad and massive… he is scarcely of the middle height and somewhat rotund; but his chest is broad and well thrown out… strong, active and muscular… his head is a formidable-looking engine; it is as round and as stern-looking as a forty-two pounder. In fitting it on the body, the formality of a neck has been dispensed with… his face carries a whole battery; the eyes quick and piercing, the mouth firm, a characteristic of resolution. The whole aspect is far removed from the ideal standard of Caucasian beauty, but it is stamped with power… his words are marshalled by the best grammatical discipline… he succeeds in making himself thoroughly understood.”

Amo was an immigrant. I once discussed the subject of immigration with him in general terms. He said the British were very welcoming and he thought, perhaps, too generous towards immigrants. I was told he had himself sold newspapers on the streets of Dublin to pay for his medical education, but I cannot verify that.

He had a wonderful, high-pitched laugh and, to me, he was kindness personified. He took over supervision of my thesis mid-stream, and his main contribution was to persuade and show me it is not sufficient to pursue excellence in the lab, but necessary also to seek perfection in writing up the data.

Here was a man, head of department and fellow of the Royal Society, in the twilight of his career, who would take me into his Senate House flat on Saturday mornings to go through my draft thesis. The routine was, he would sit me down, switch on the television to watch the wrestling, disappear for an hour or so, then we would get to work.

He might spend an hour on two pages of A4 typescript, double spaced – to correct the English. This led initially to a rather florid style – for example, “notwithstanding the inherent simplicity of this hypothesis” but, in the longer term, my style quietened and his tutelage proved to be invaluable.

In the 1960s, it was the norm for the supervisor to be the internal examiner for PhD vivas and, for me, he selected Mary Pickford, of The University of Edinburgh, as external examiner. She was another gifted scientist and it would be of interest to me to know if I was, and am, the only RVC PhD student to be examined by two Royal Society fellows. Fortunately, all was well.