Coco – a two-year-old female, neutered springer spaniel – is presented to you unable to bear weight on her pelvic limbs for a period of 24 hours.

The owners report that Coco had seemed off colour for the previous two weeks, and had showed signs of a hunched stance, reluctance to walk and hindlimb stiffness. She had been seen by another vet, who had obtained radiographs of the thoracolumbar spine, but these had appeared unremarkable.

Coco had been prescribed meloxicam 0.1mg/kg once daily and had initially seemed to improve a little, but had subsequently deteriorated again.

In addition, the owners report that Coco had had a period of left forelimb lameness around two months earlier that had resolved following removal of a small grass seed from between her digits.

On examination Coco is bright, but unable to bear weight on her pelvic limbs. Paraplegia is evident, with normal forelimb function and no evidence of any intracranial disease.

Pelvic limb conscious proprioceptive reactions are absent, but nociception is intact. The tail sensation and anal tone are normal, and the panniculus reflex is intact bilaterally. Segmental spinal reflexes are intact. No evidence of discomfort exists on palpation of the thoracolumbar spine. The remainder of the physical examination is unremarkable.

Question

What is your neuro-localisation and your differential diagnoses?

Answer

The neurological examination is consistent with a T3-L3 myelopathy. Differential diagnoses include intervertebral disc disease, neoplasia and inflammatory conditions such as meningitis or discospondylitis. Given the historical features, other conditions such as a degenerative myelopathy, ischaemic myelopathy or trauma are less likely.

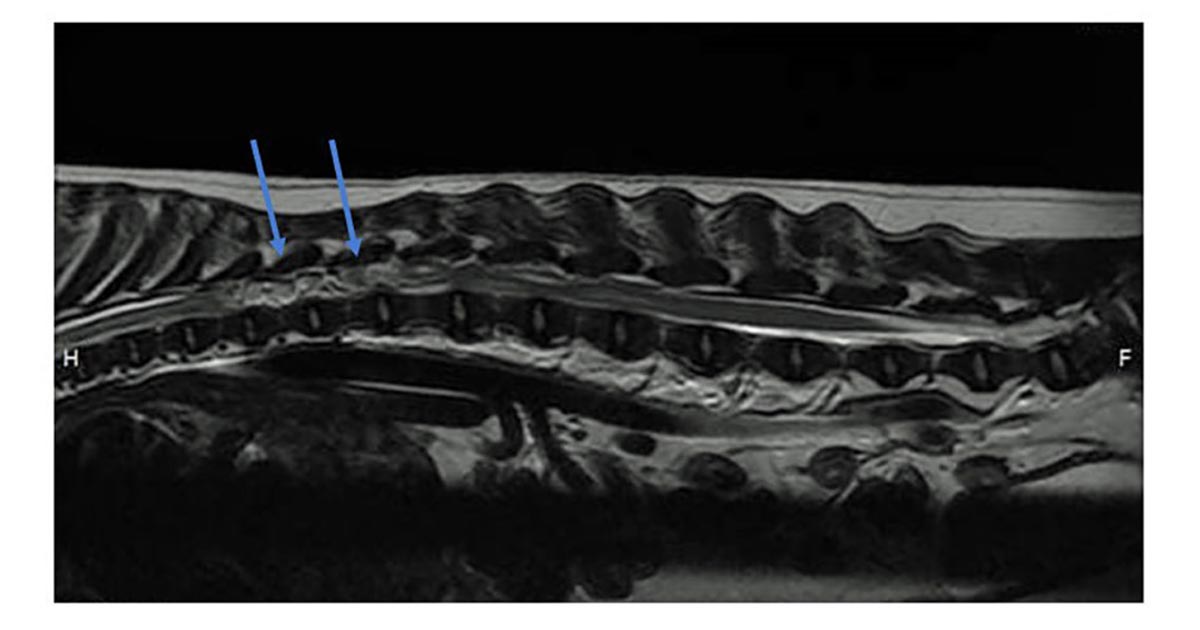

In this case, an MRI scan of the thoracolumbar spine was performed. This revealed moderate-marked extradural compression and left side spinal cord displacement extending from T9-10 to L2-3. Furthermore, heterogeneous hyperintense changes were noted affecting the adjacent hypaxial musculature (Figure 1).

Epidural empyema secondary to a migrating sublumbar foreign body was suspected. Surgery was scheduled for the same day. A dorsal approach was made to the thoracolumbar spine and a dorsal laminectomy performed from T10-L2.

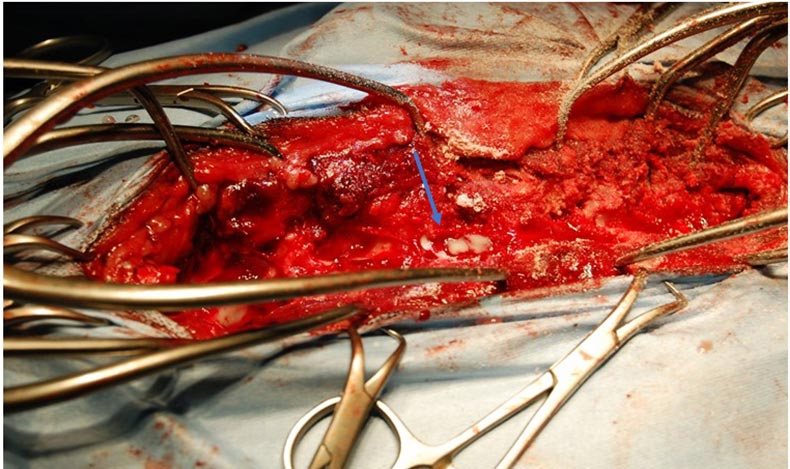

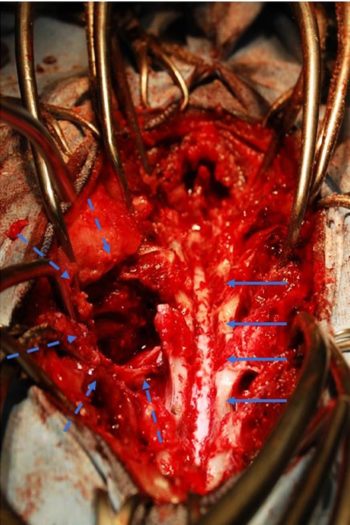

A large volume of purulent material was retrieved, allowing decompression of the spinal cord. A tract was noted running from the left T13-L1 intervertebral foramen to the sublumbar region; exploration of this revealed several large pockets of purulent material affecting the sublumbar region, which were debrided.

The surgical site was irrigated with large volumes of Hartmann’s solution prior to routine closure. Samples were submitted for bacteriology; this revealed the presence of an anaerobic coccobacillus, which was sensitive to clavulanate potentiated amoxicillin (Figures 2 and 3).

Coco was hospitalised following surgery and after six days was able to walk with minimal assistance, and passed both urine and faeces voluntarily. She was discharged with a course of clavulanate potentiated amoxicillin 250mg twice daily for four weeks, meloxicam 0.1mg/kg once daily for two weeks and gabapentin 10mg/kg three times daily for one week.

At a check-up six weeks following surgery, the owners reported that Coco was able to exercise normally. On examination she was able to walk and trot well, although mild left pelvic paresis was present.

Discussion

Epidural empyema is defined as an accumulation of purulent material in the epidural space of the vertebral canal (Dewey et al, 1998). This condition can produce signs ranging from spinal pain, reported in this case from the referring veterinary surgeon, to general malaise, pyrexia, vomiting and lethargy.

Epidural empyema can have different potential sources and may be associated with osteomyelitis, discospondylitis, paraspinal abscess and migrating foreign bodies. In addition, it has been reported as a complication lumbosacral epidural analgesic, although this is rare (Lavely et al, 2006; Volk et al, 2005).

Treatment of epidural empyema can be either medical or surgical (Lavely et al, 2006). Medical treatment consists in the administration of IV antibiotics that can cross the cerebrospinal fluid barrier, and is ideally based on culture and sensitivity results. Antibiotics are normally continued for several months after clinical signs have resolved (Monteiro et al, 2016).

In cases of refractory response to antibiotics or those with more significant neurological deficits, surgical decompression via dorsal laminectomy can be performed (De Stefani et al, 2008). In this case, surgery was chosen as a first line treatment due to the rapidly deteriorating neurological status and the degree of marked compression of the spinal cord.

The prognosis of spinal empyema is somewhat variable. Many patients will respond to appropriate antibiotic therapy without surgical intervention. Relapses represent the most common complication encountered and antibiotic treatment lasting for several months is therefore advisable.

Non-responsive patients may require surgical treatment including surgical decompression and lavage of the affected spinal cord site. In human medicine, surgical drainage was previously considered the treatment of choice for this condition (Pinkington et al, 2003).

Currently, up to 50 per cent of human patients are treated medically as the mortality rate seems to be higher in those patients that underwent surgery, although the reasons for this are unclear (Reihsaus et al, 2000; Siddiq et al, 2004; Karikari et al, 2009).

In one paper, medical management was described to treat five dogs with epidural empyema with clinical short-term improvement and excellent long-term outcome (Monteiro et al, 2016).

At present, no guidelines exist to help veterinary surgeons in deciding what is the most appropriate treatment for every specific patient. Guidelines can be, however, extrapolated from human medicine, which could greatly help in the decision-making process.

Human patients are selected for medical management based on various criteria, including an absence of significant neurological deficits, non-compressive spinal lesion, extensive lesions for which multiple surgical decompressive procedures would create vertebral instability, and poor anaesthetic or surgical candidates (Monteiro et al, 2016).

In our case, early surgery was performed because the patient showed rapid neurological deterioration with hindlimb paraparesis, and significant extradural compression was noted on the MRI scan. Moreover, the history of grass seed removal from the left forelimb two months earlier made the possibility of a migrating foreign body more likely.

Leave a Reply